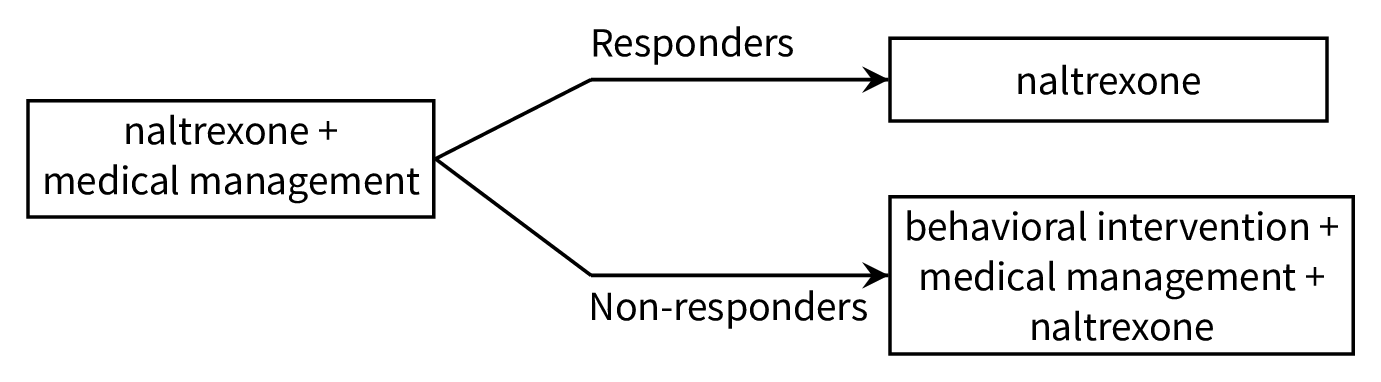

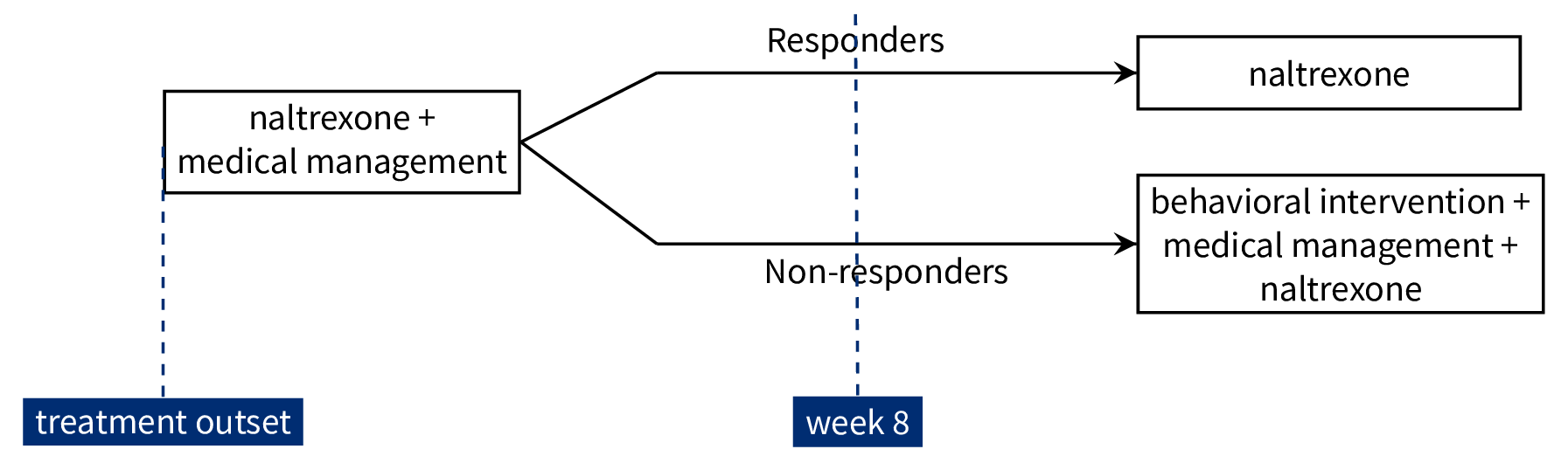

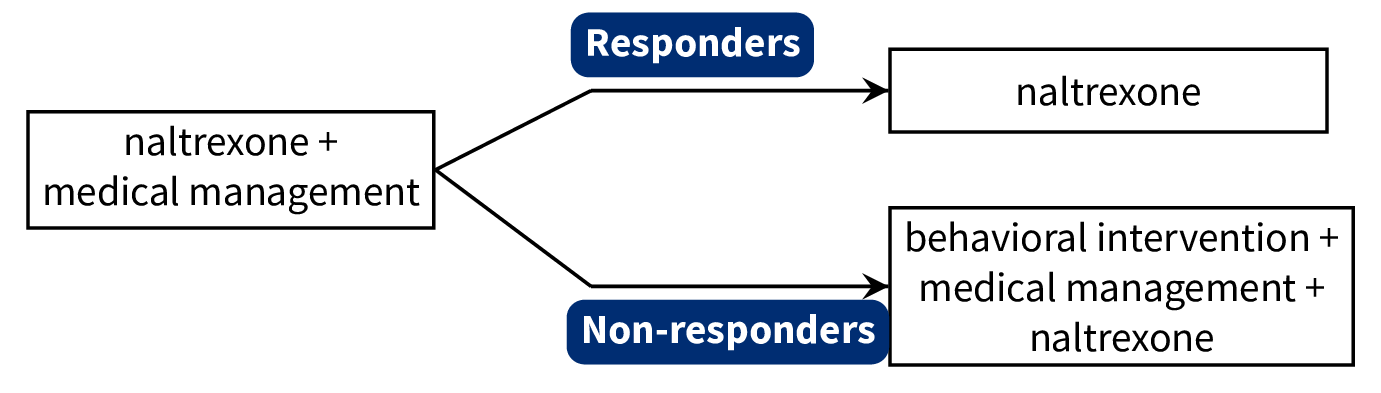

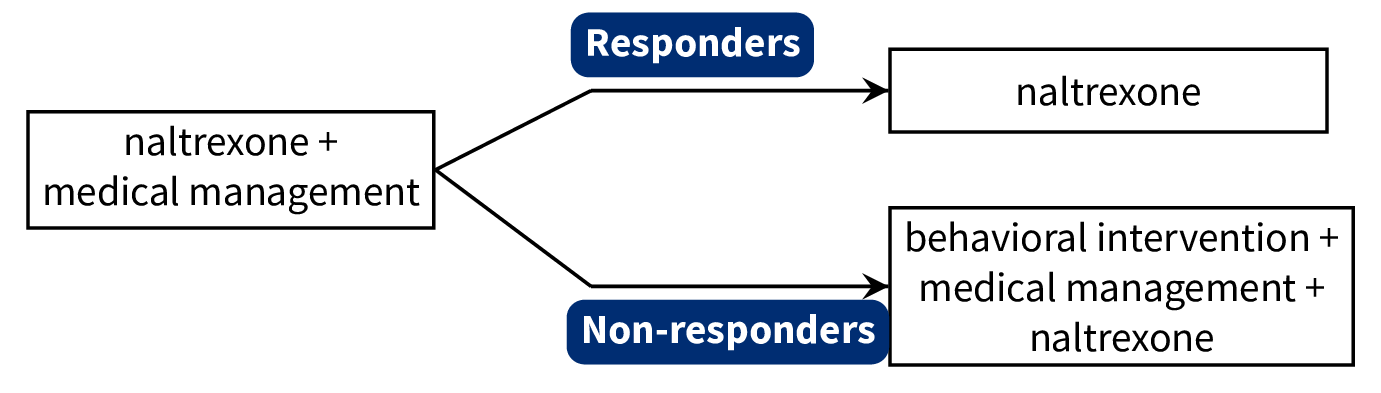

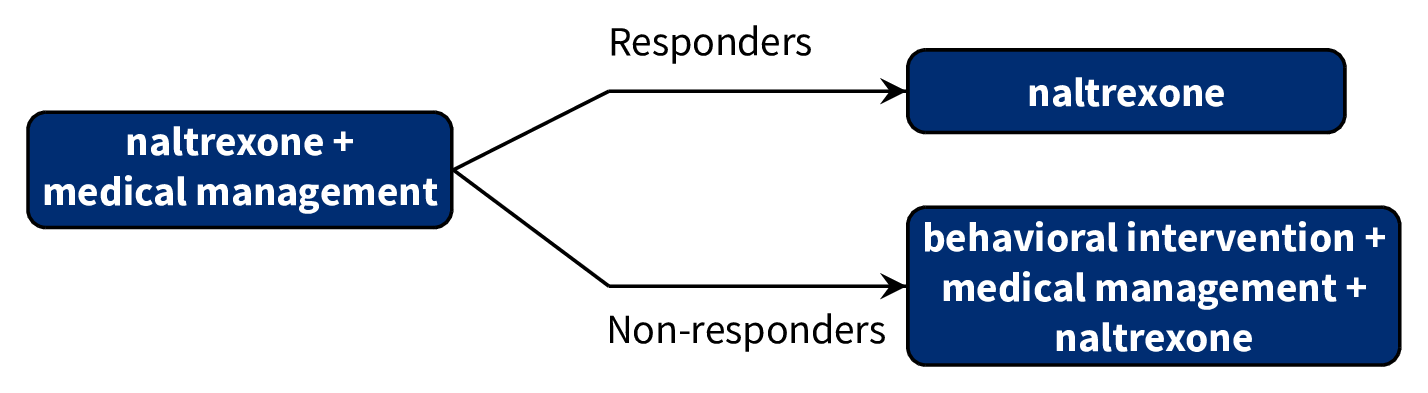

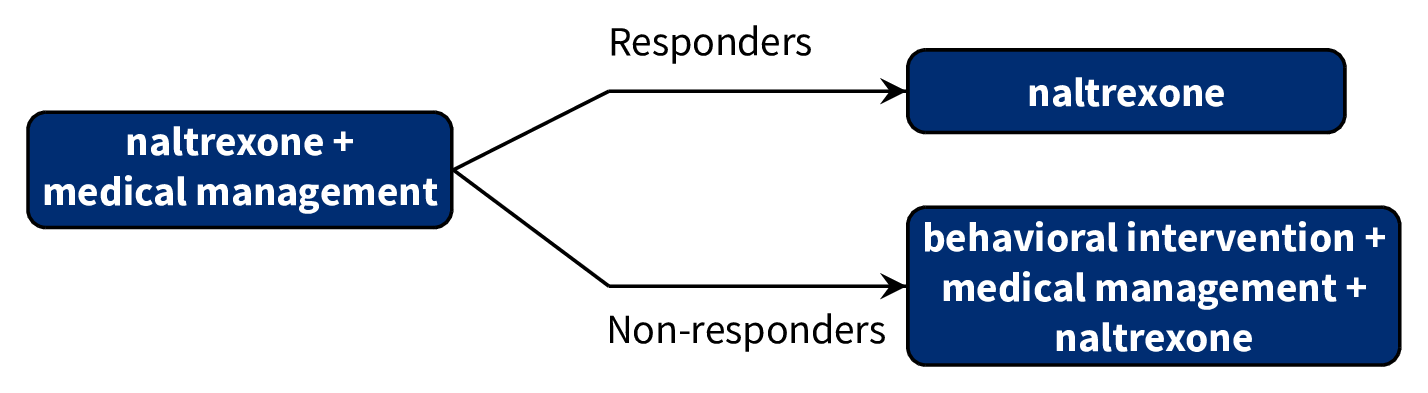

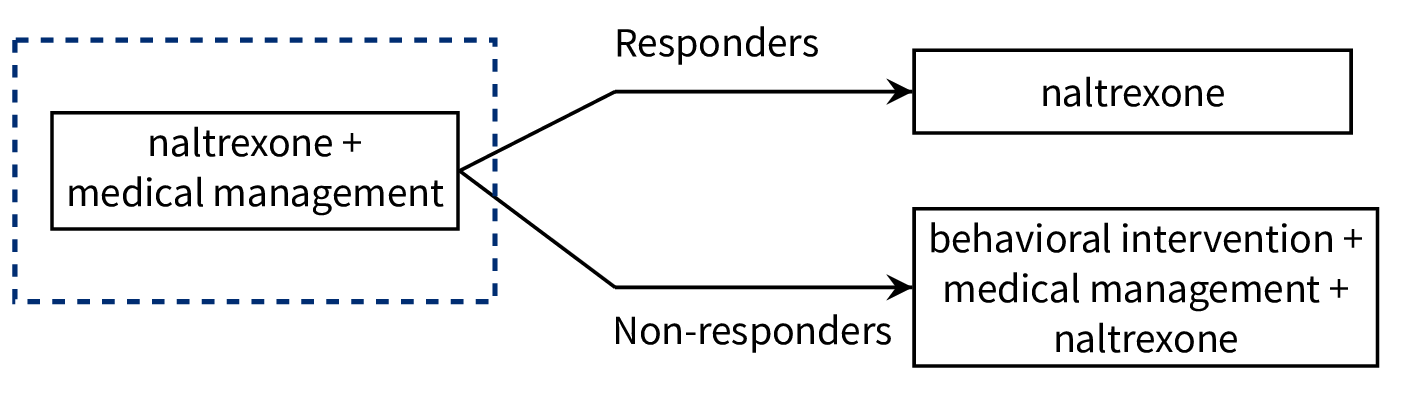

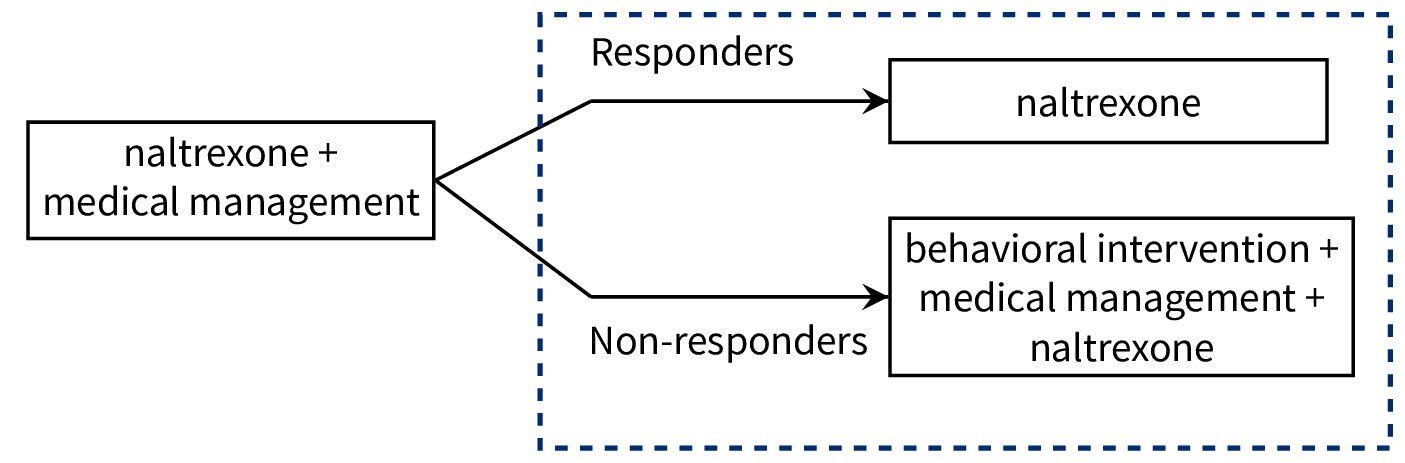

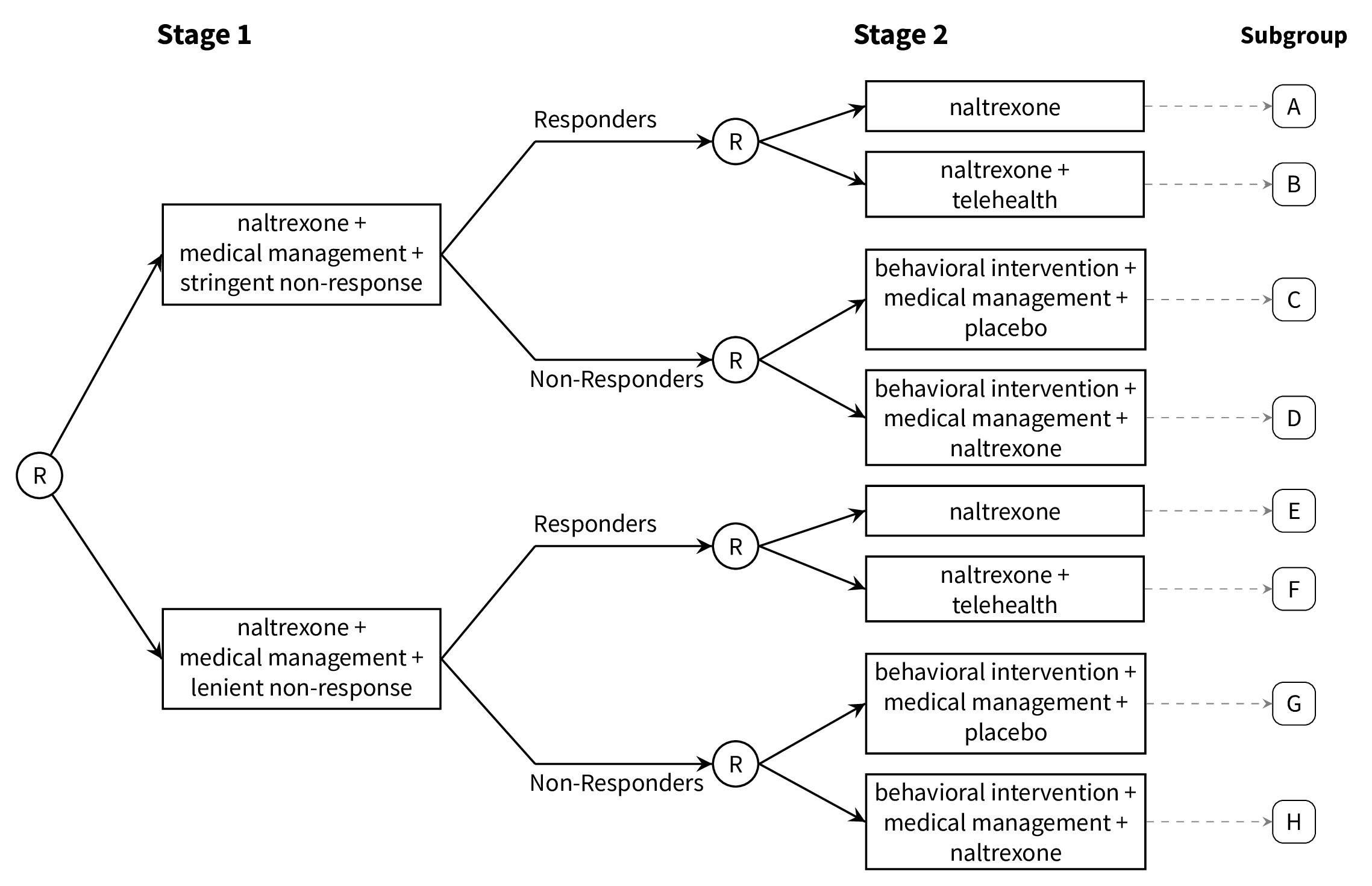

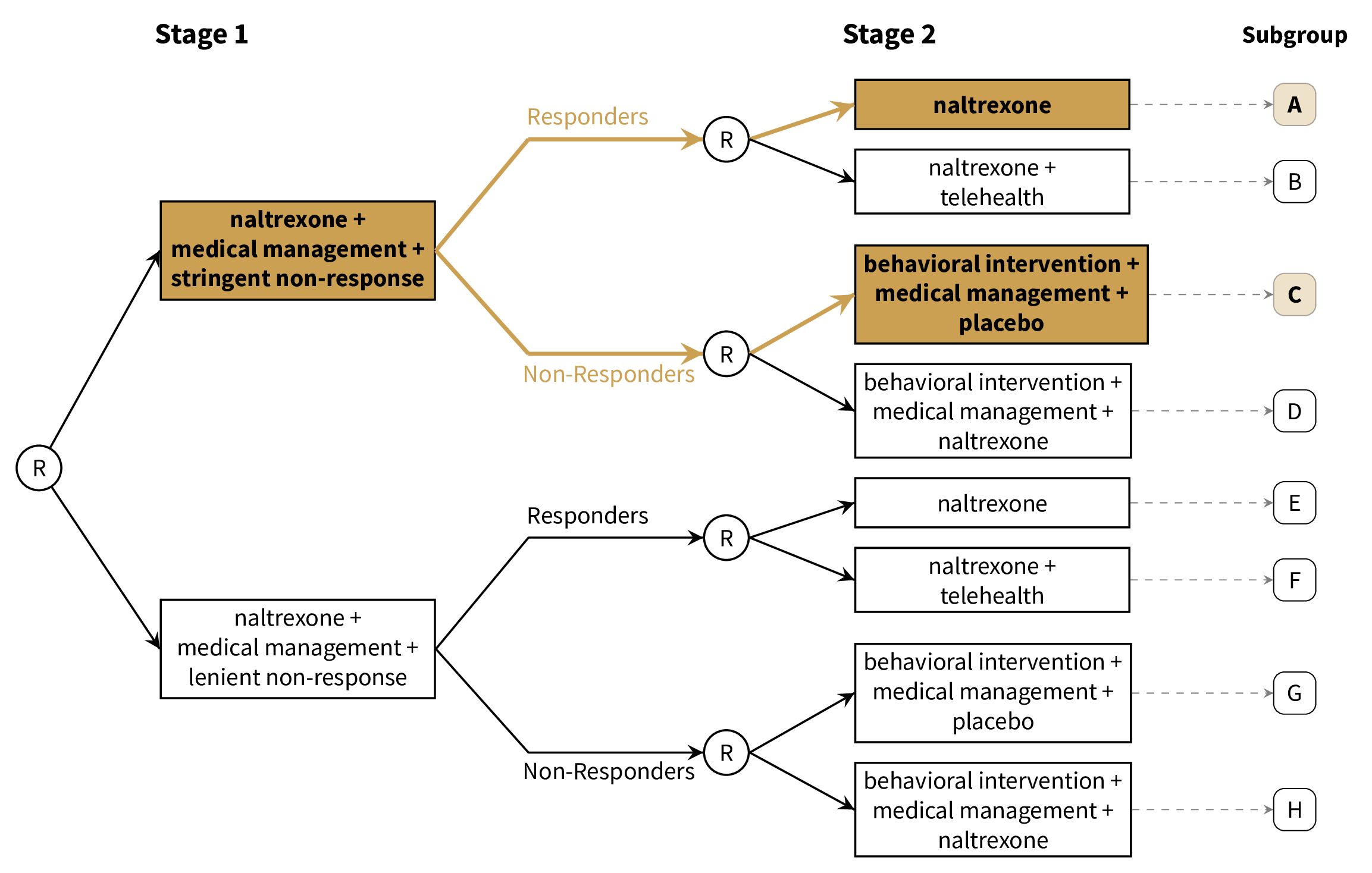

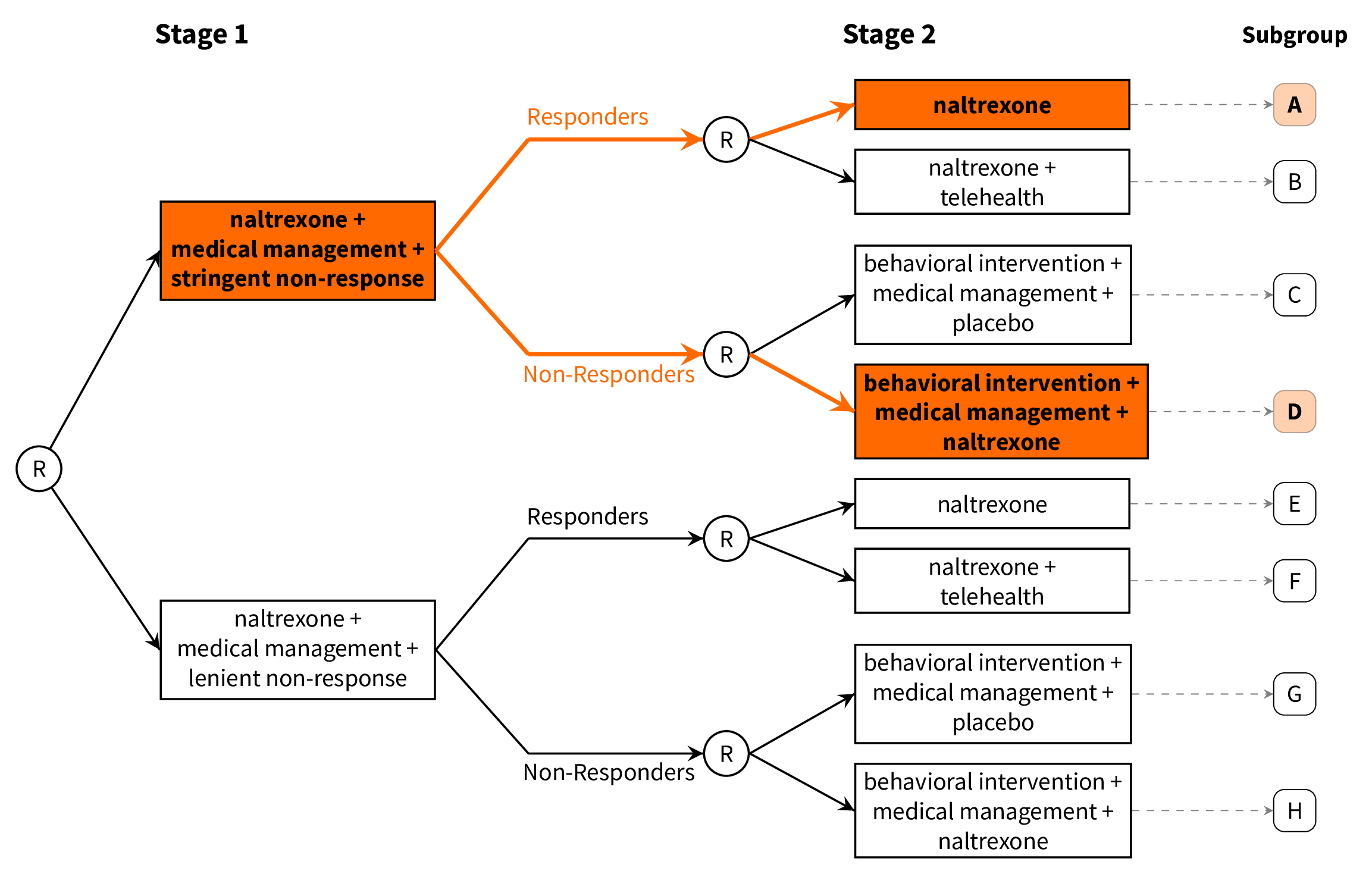

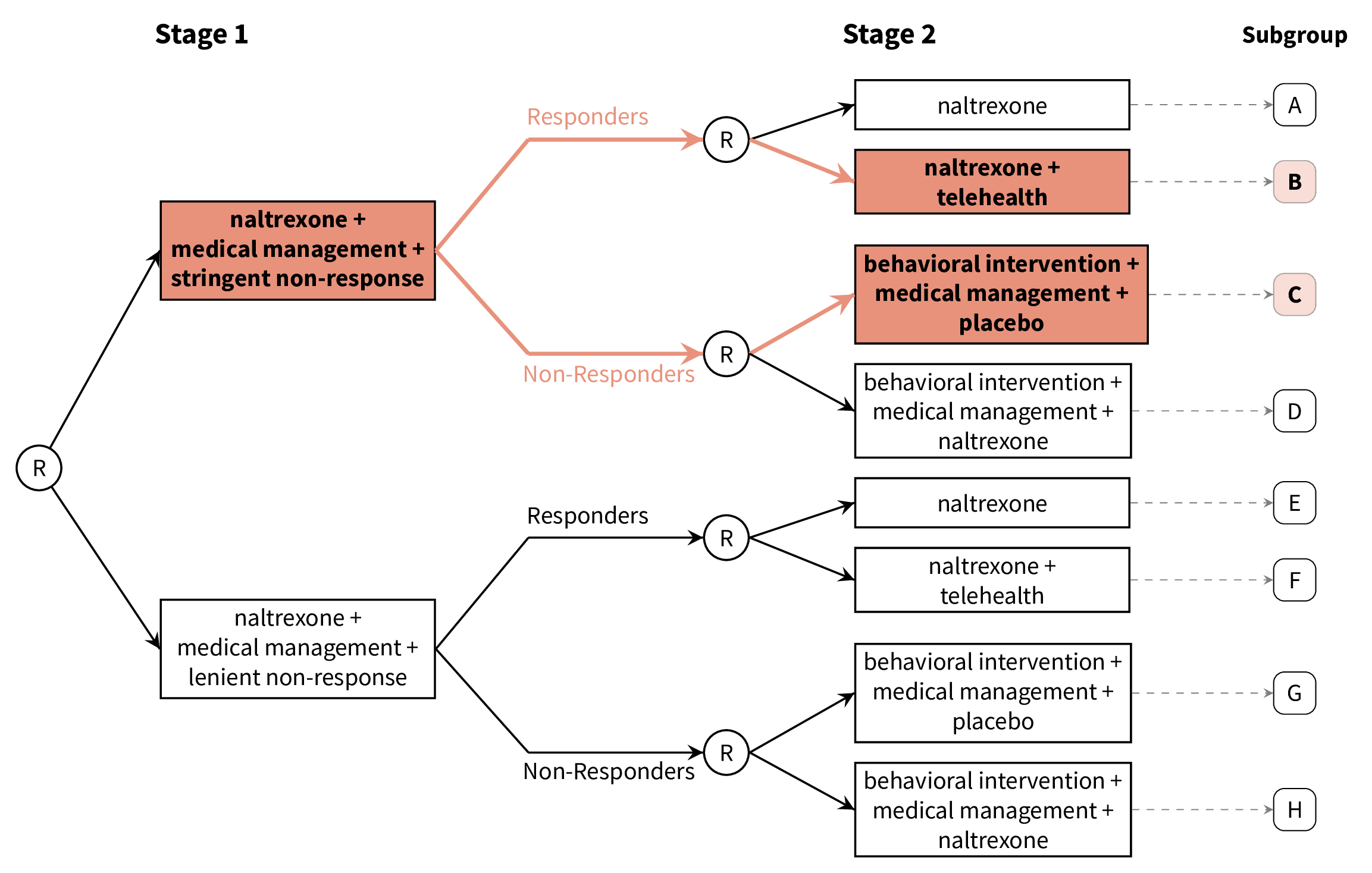

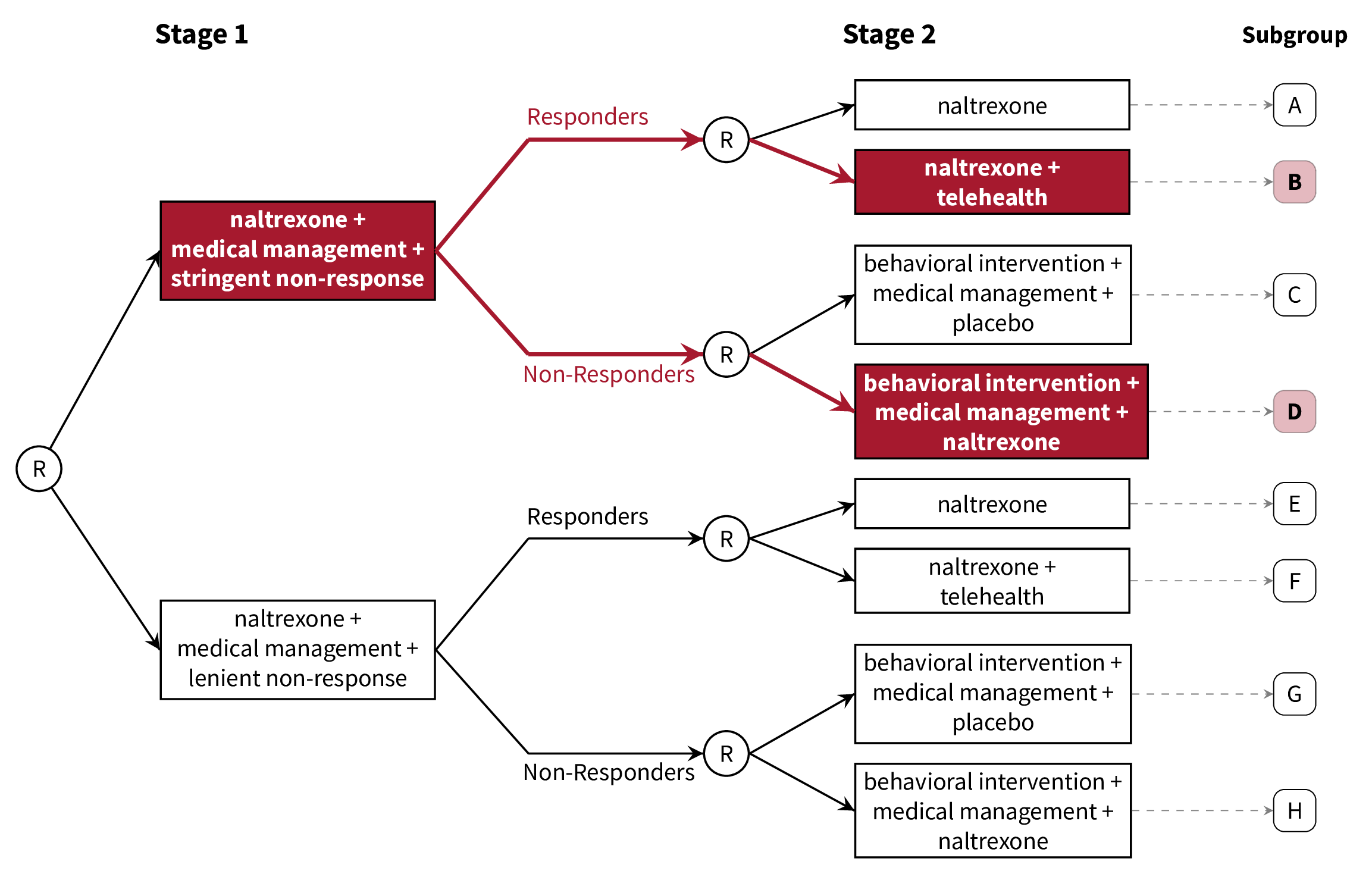

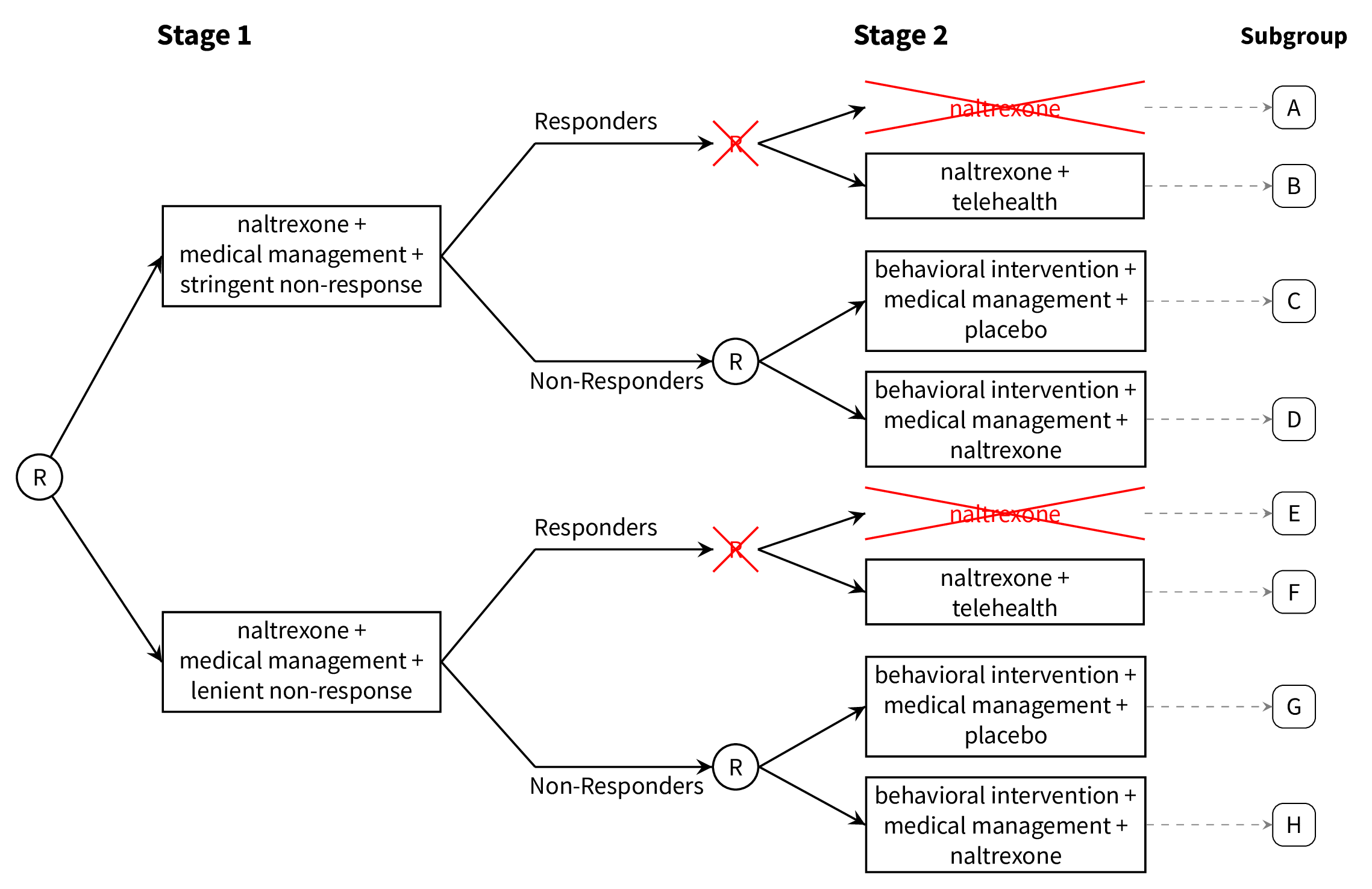

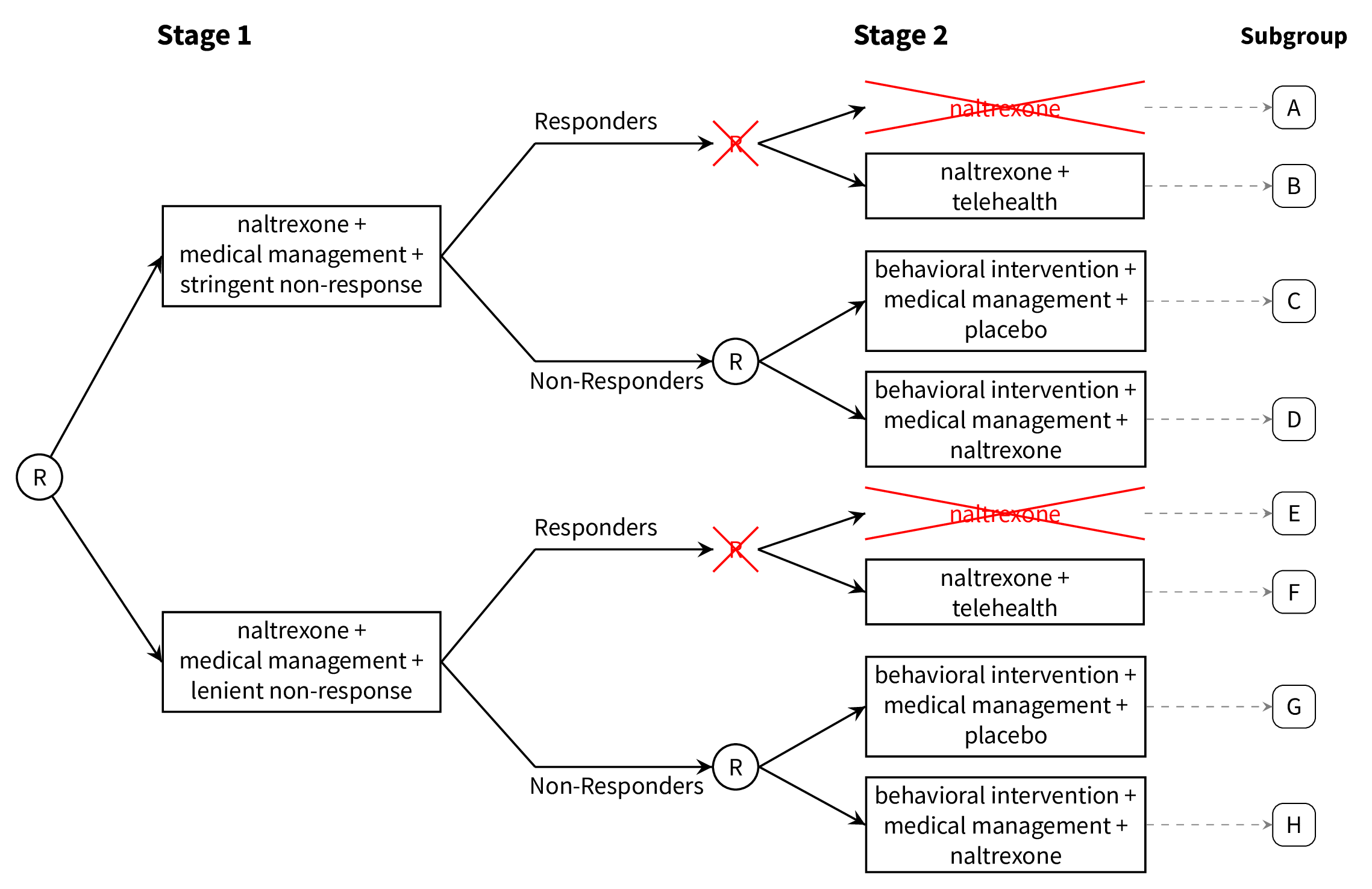

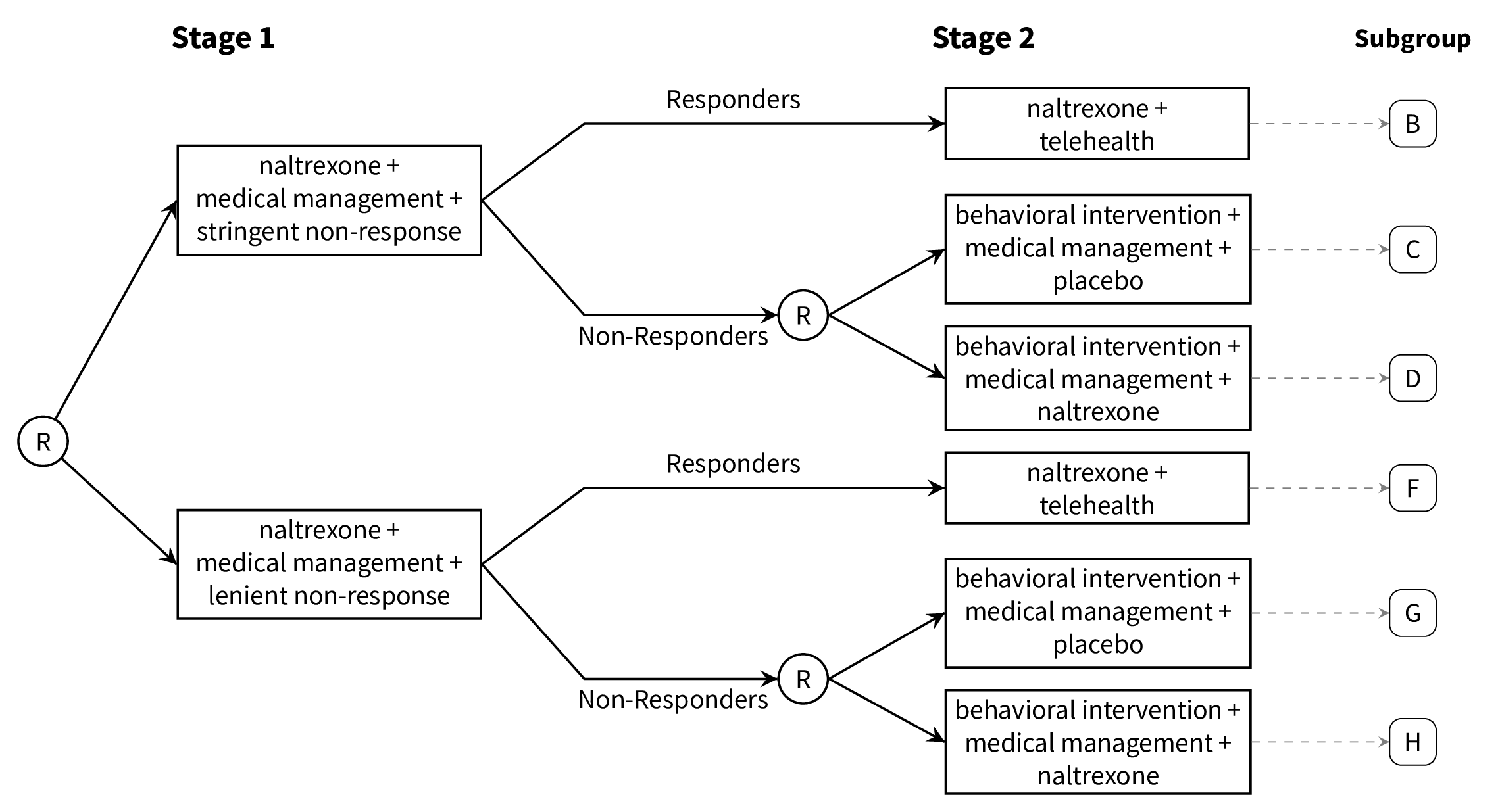

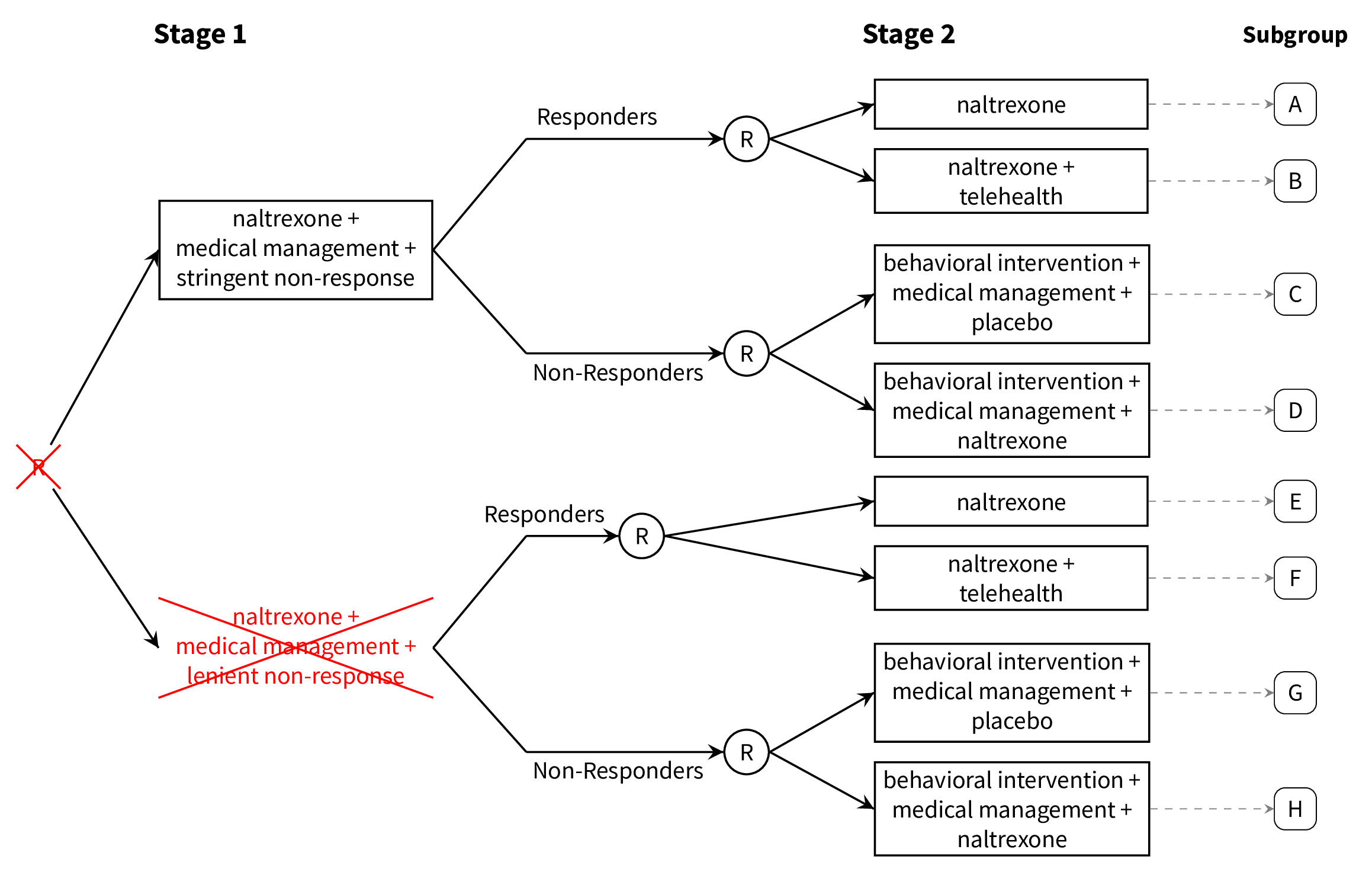

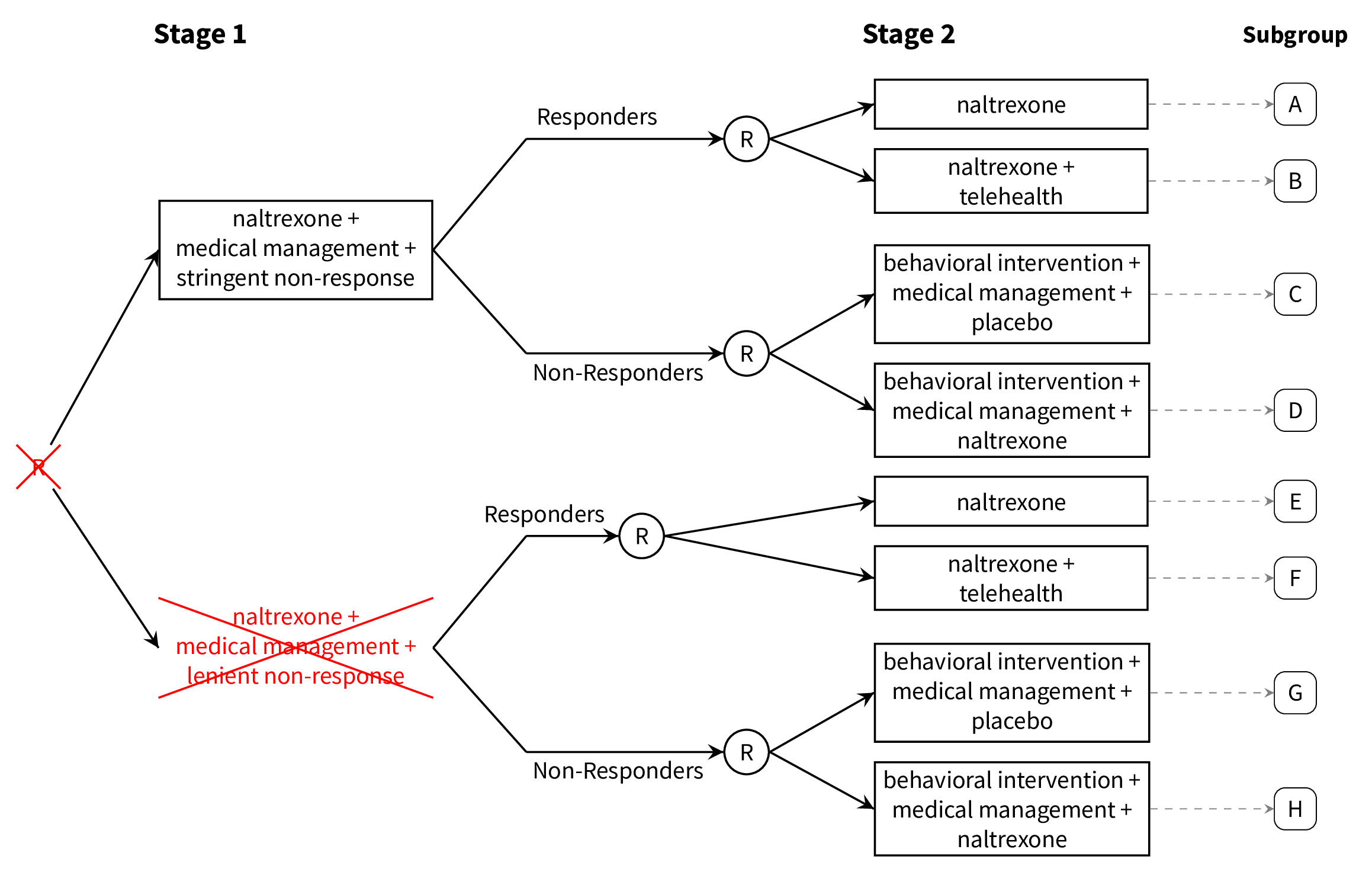

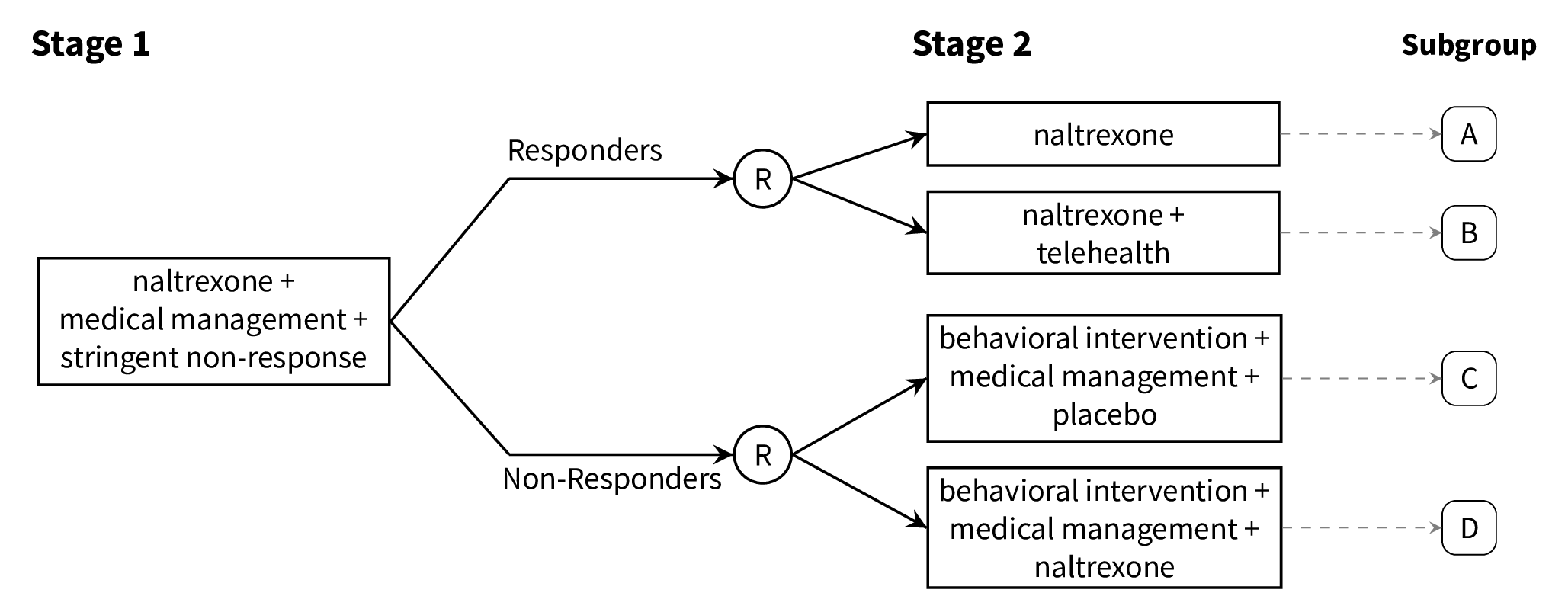

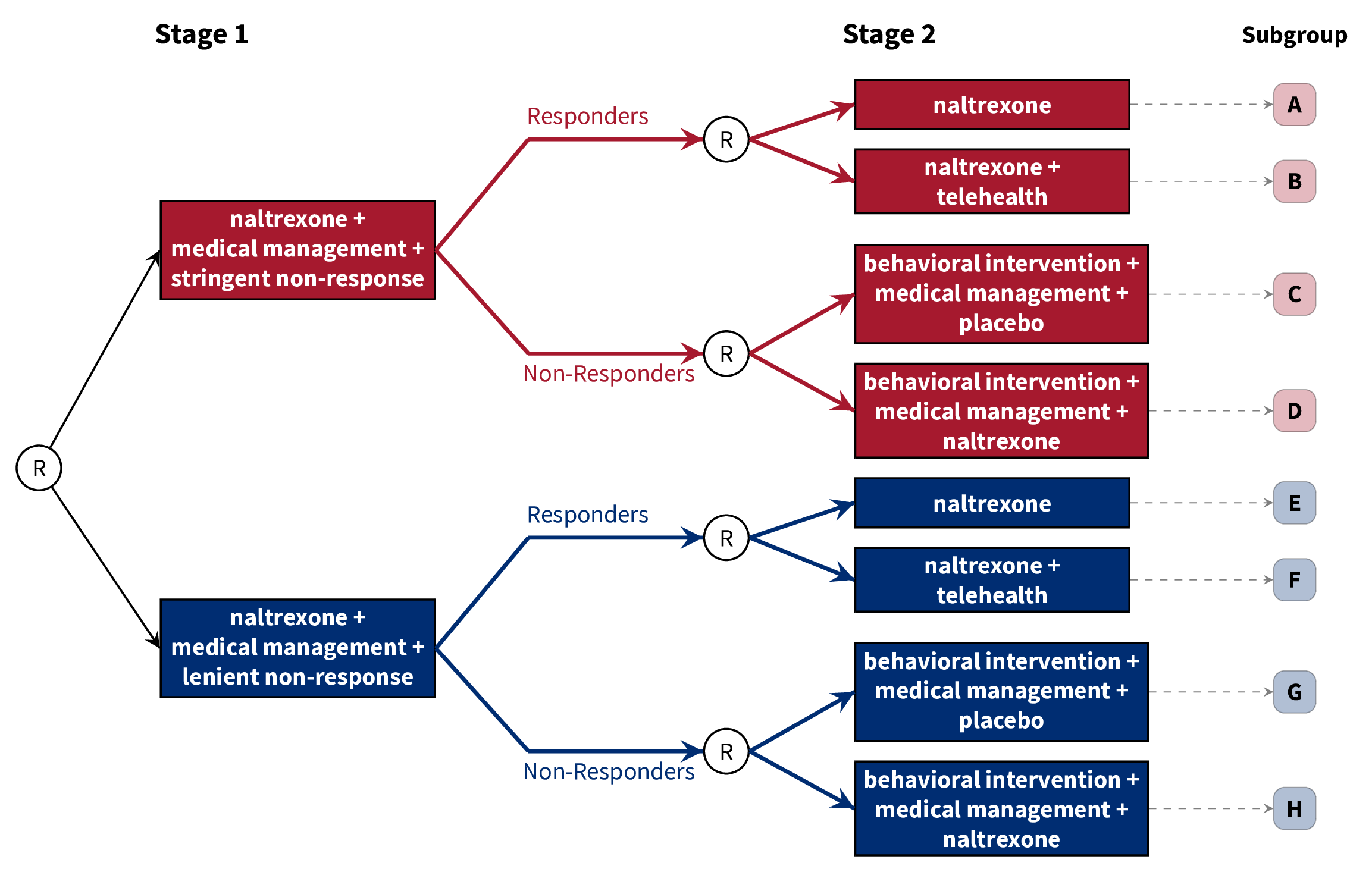

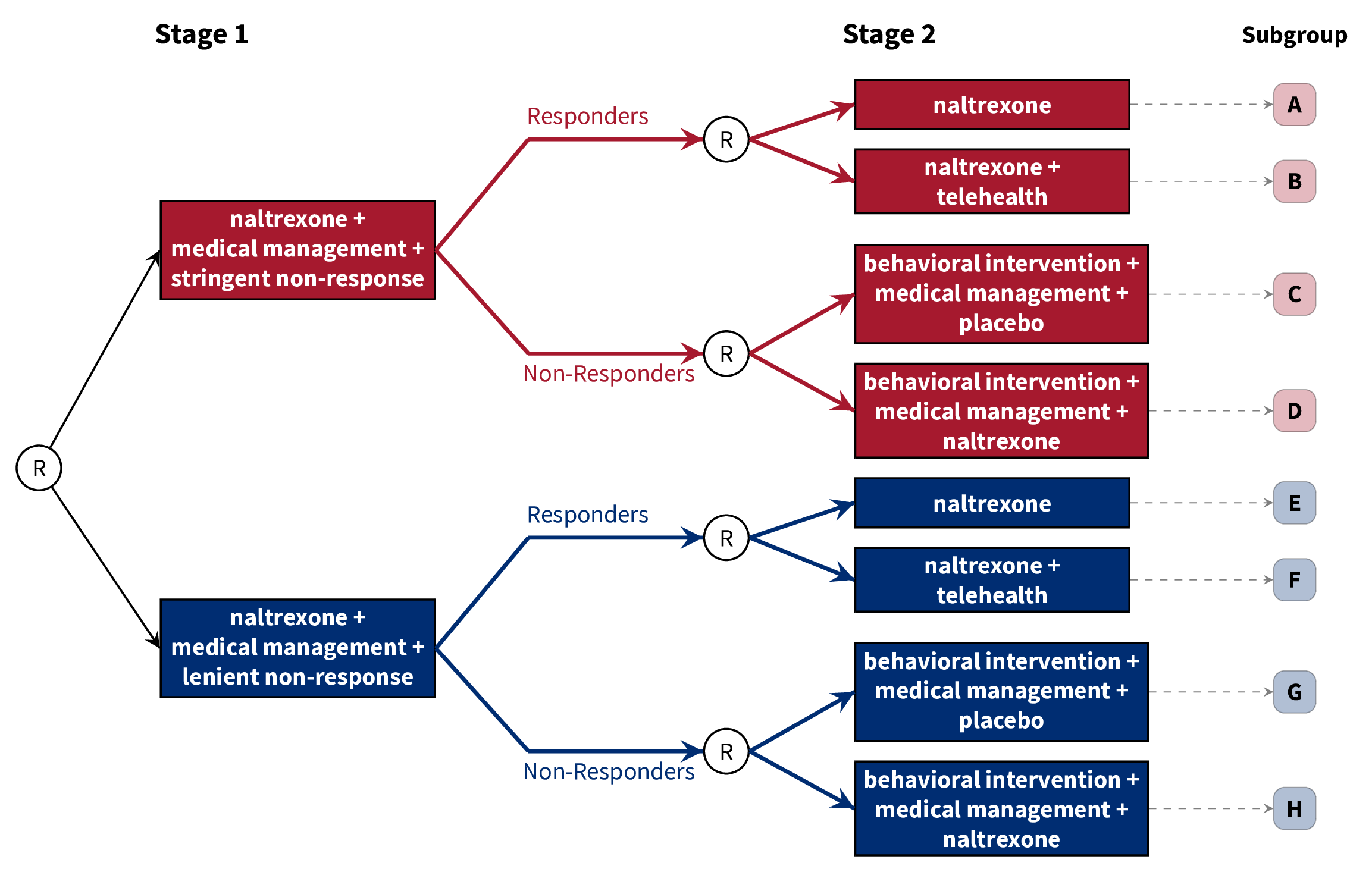

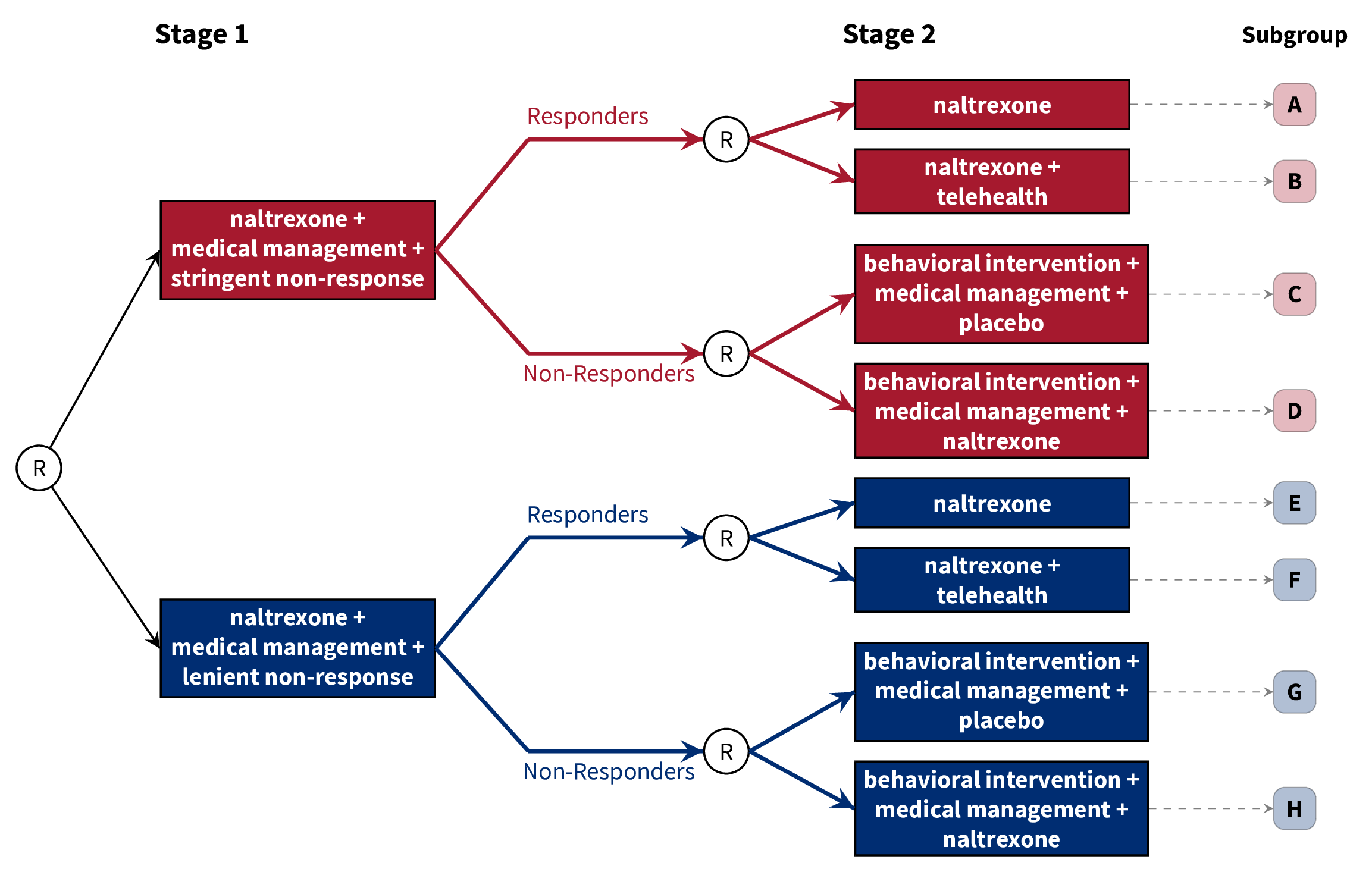

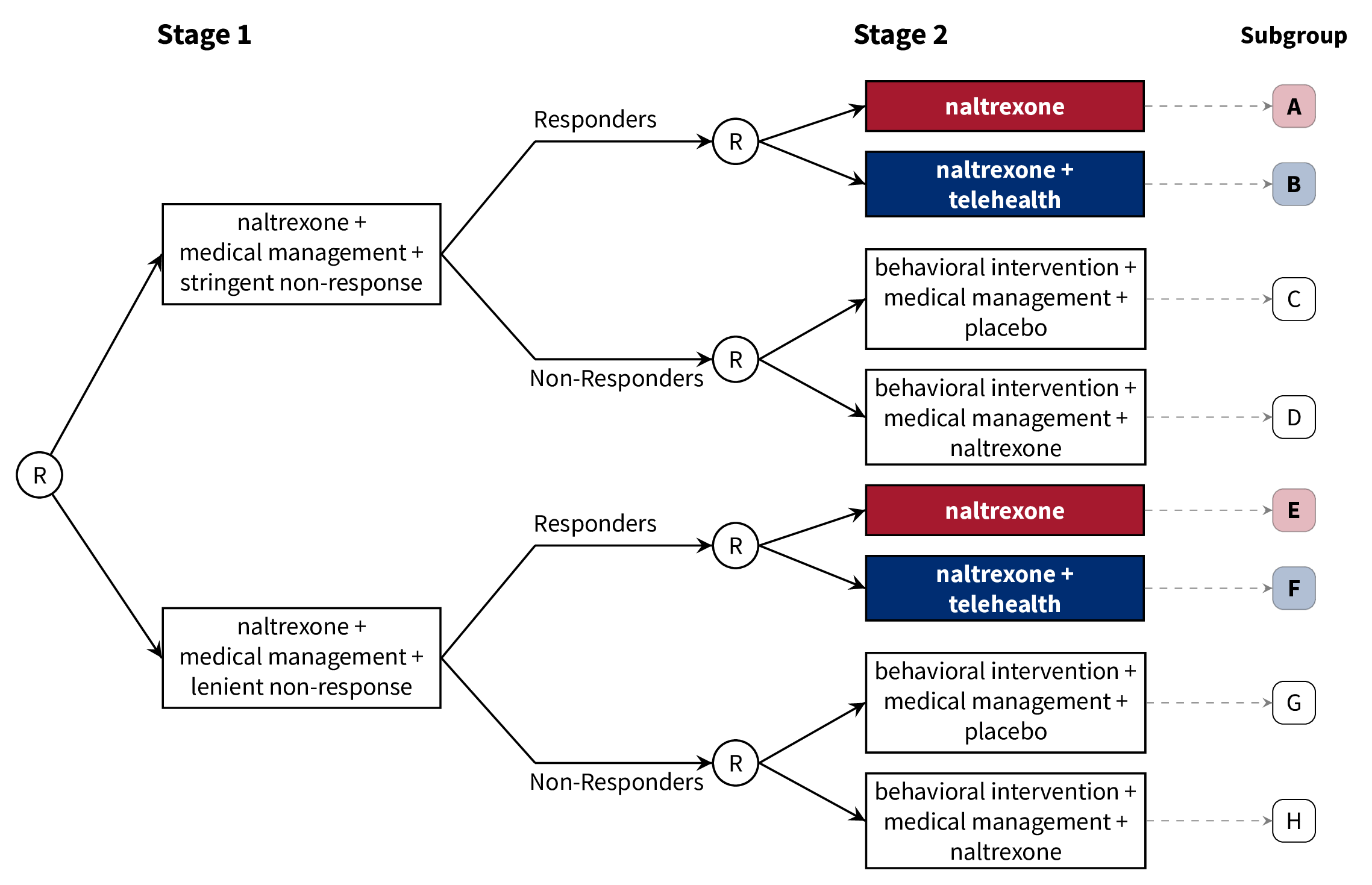

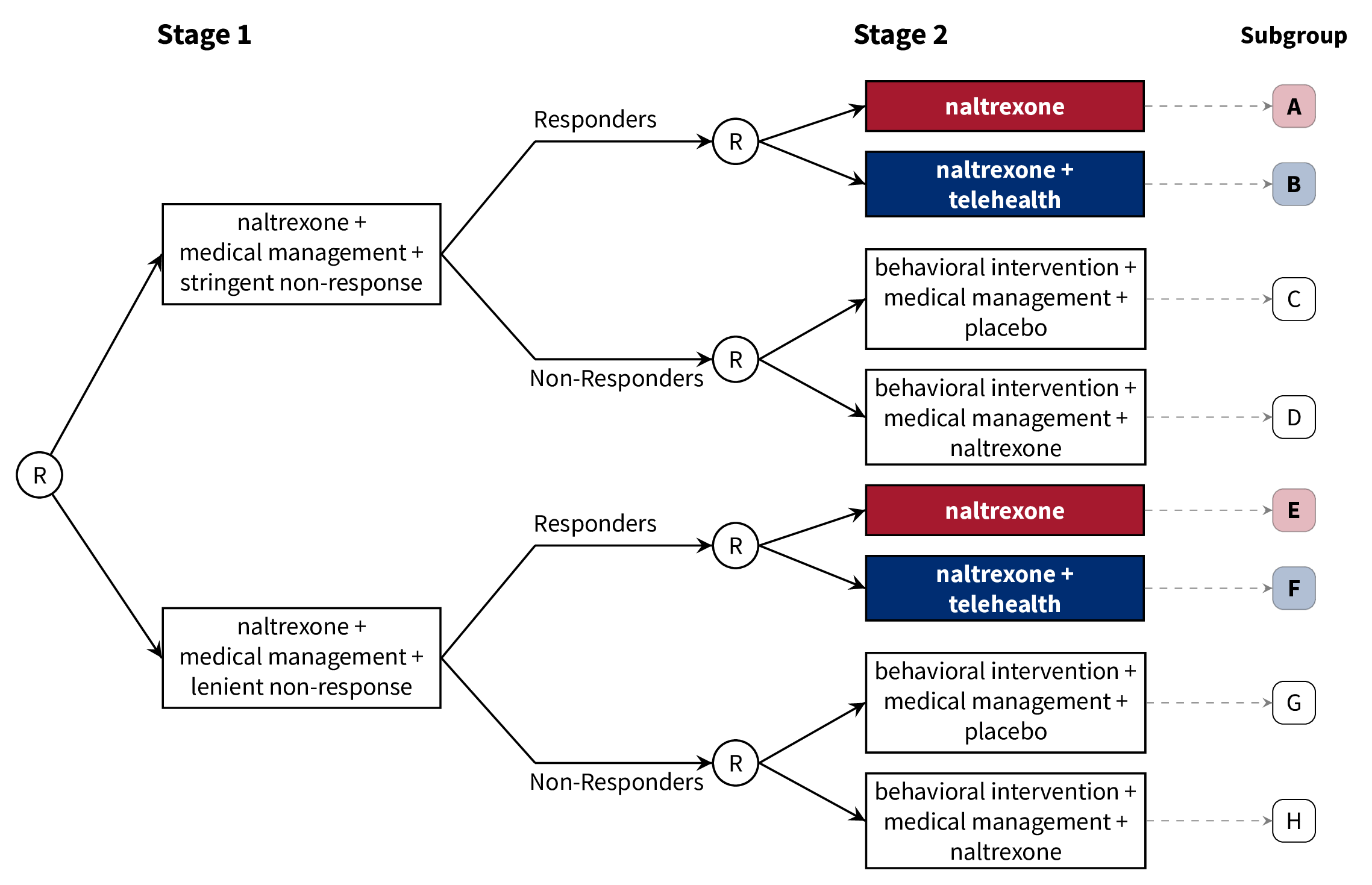

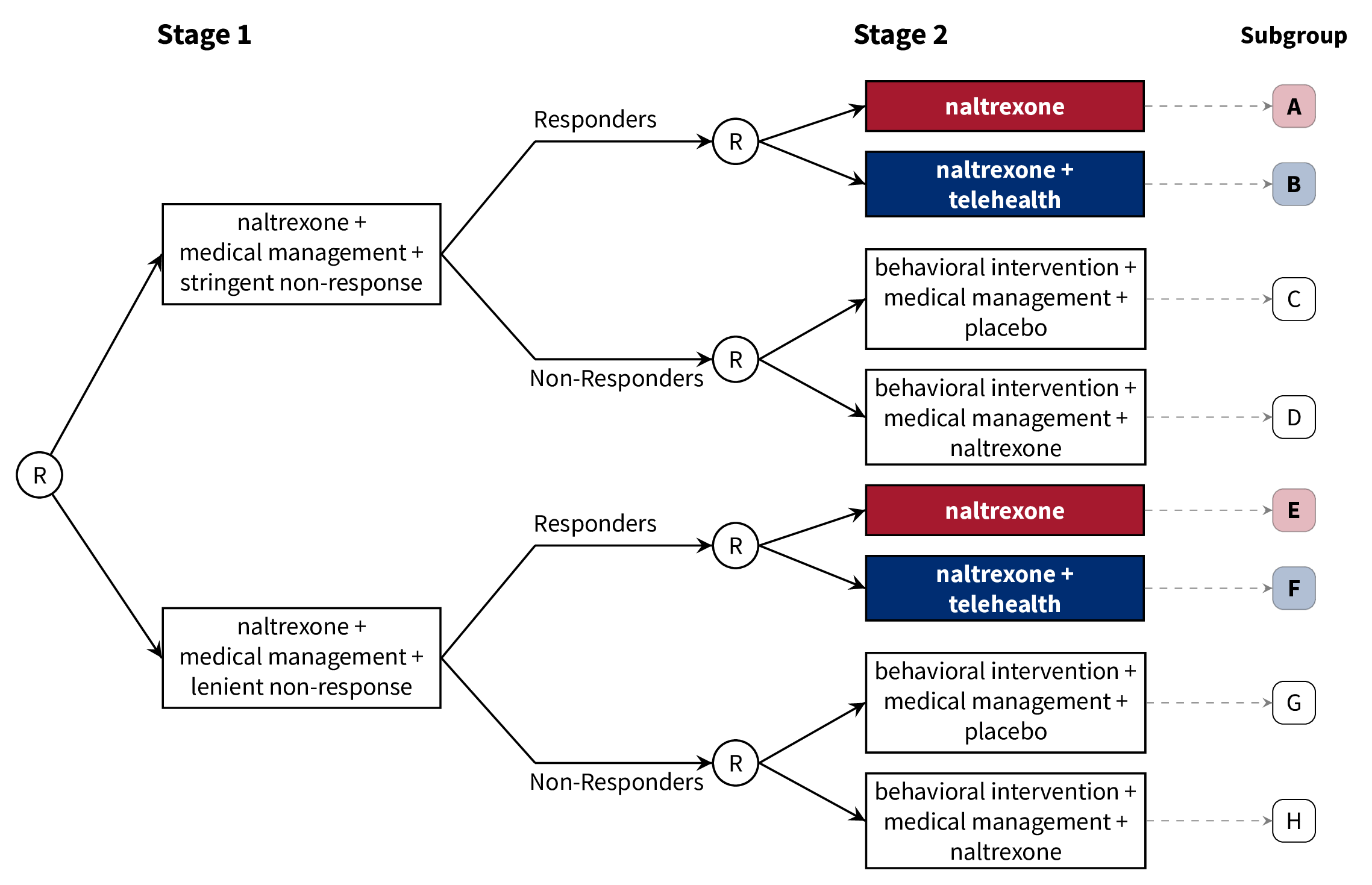

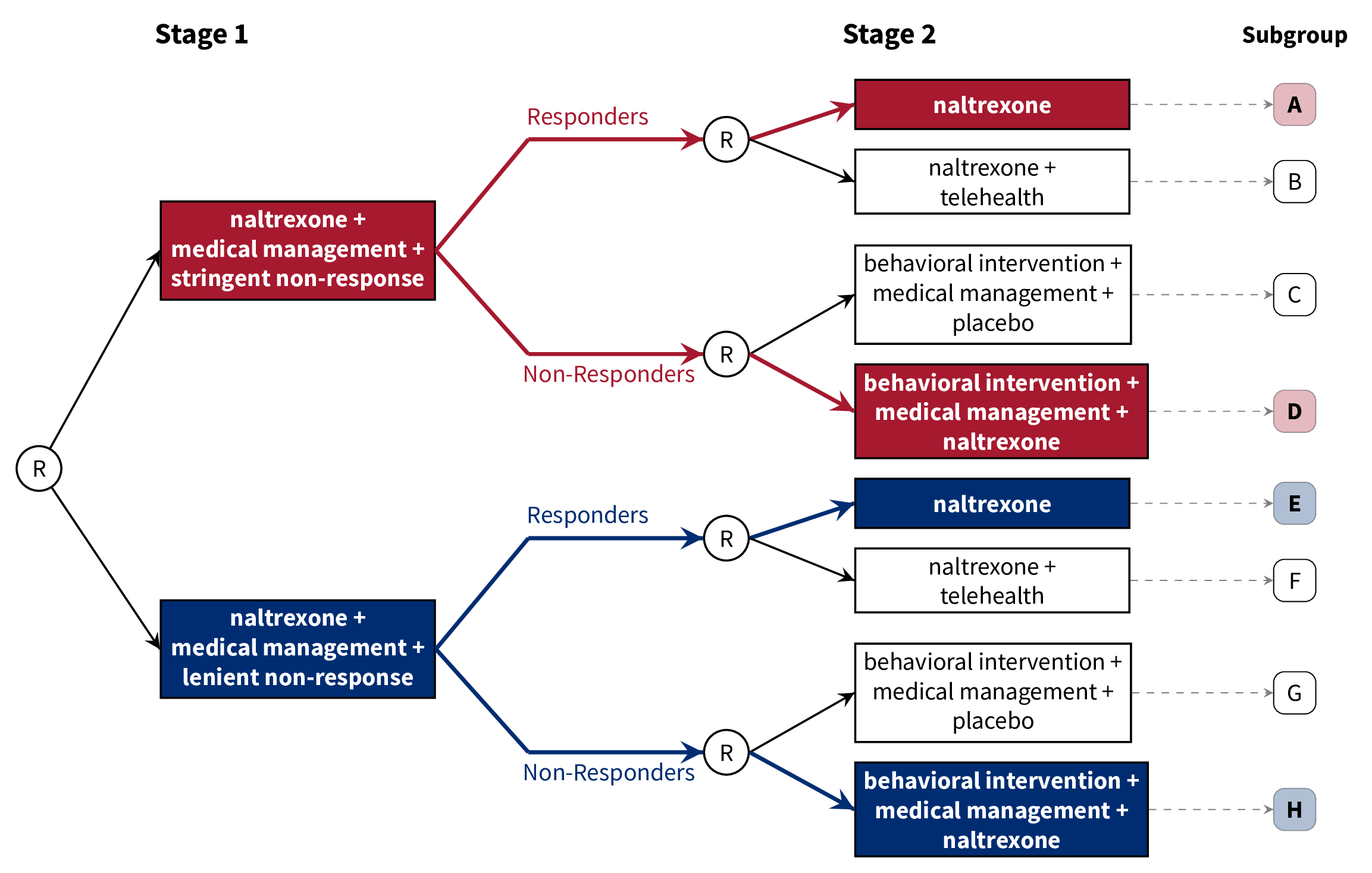

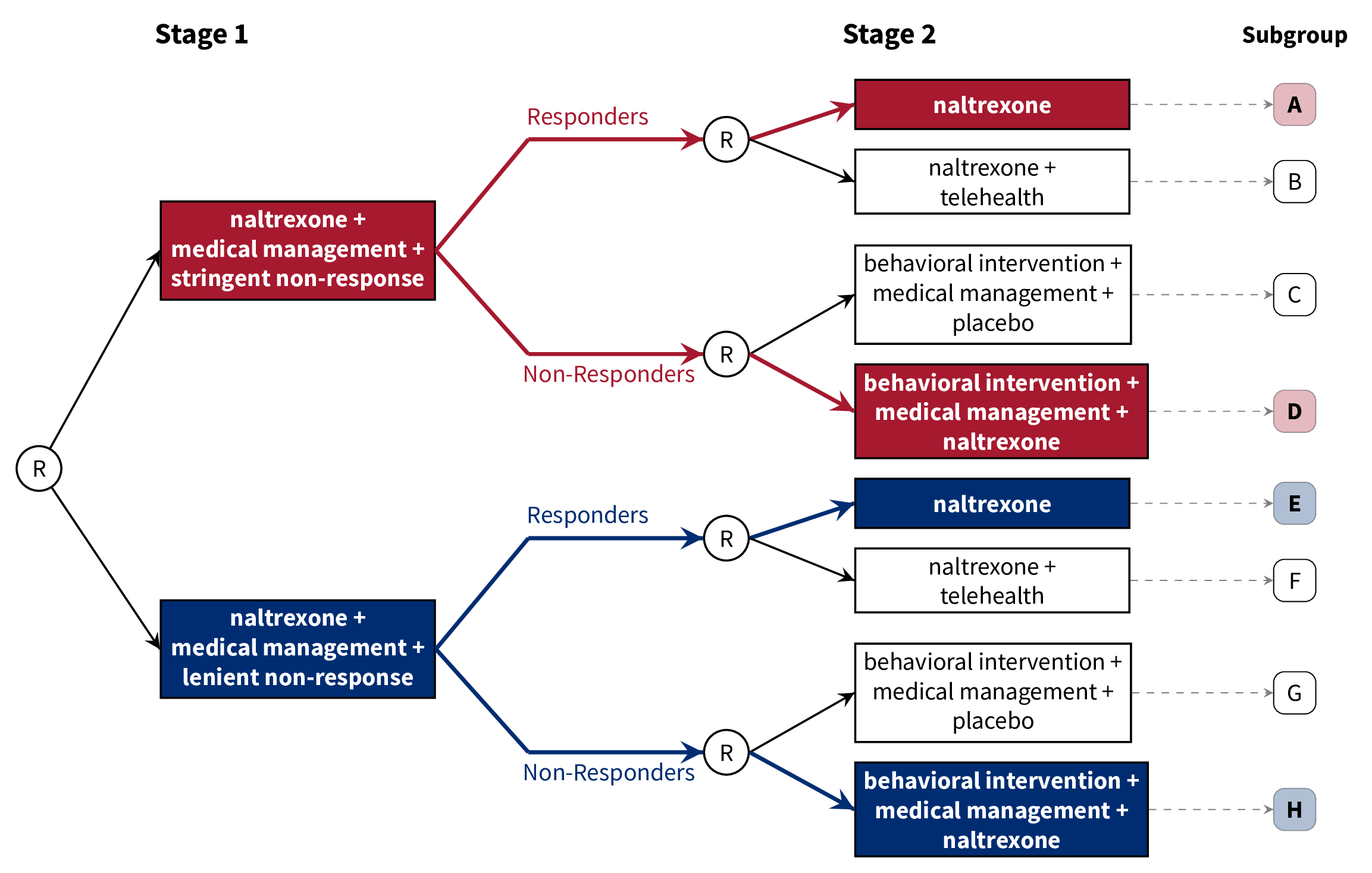

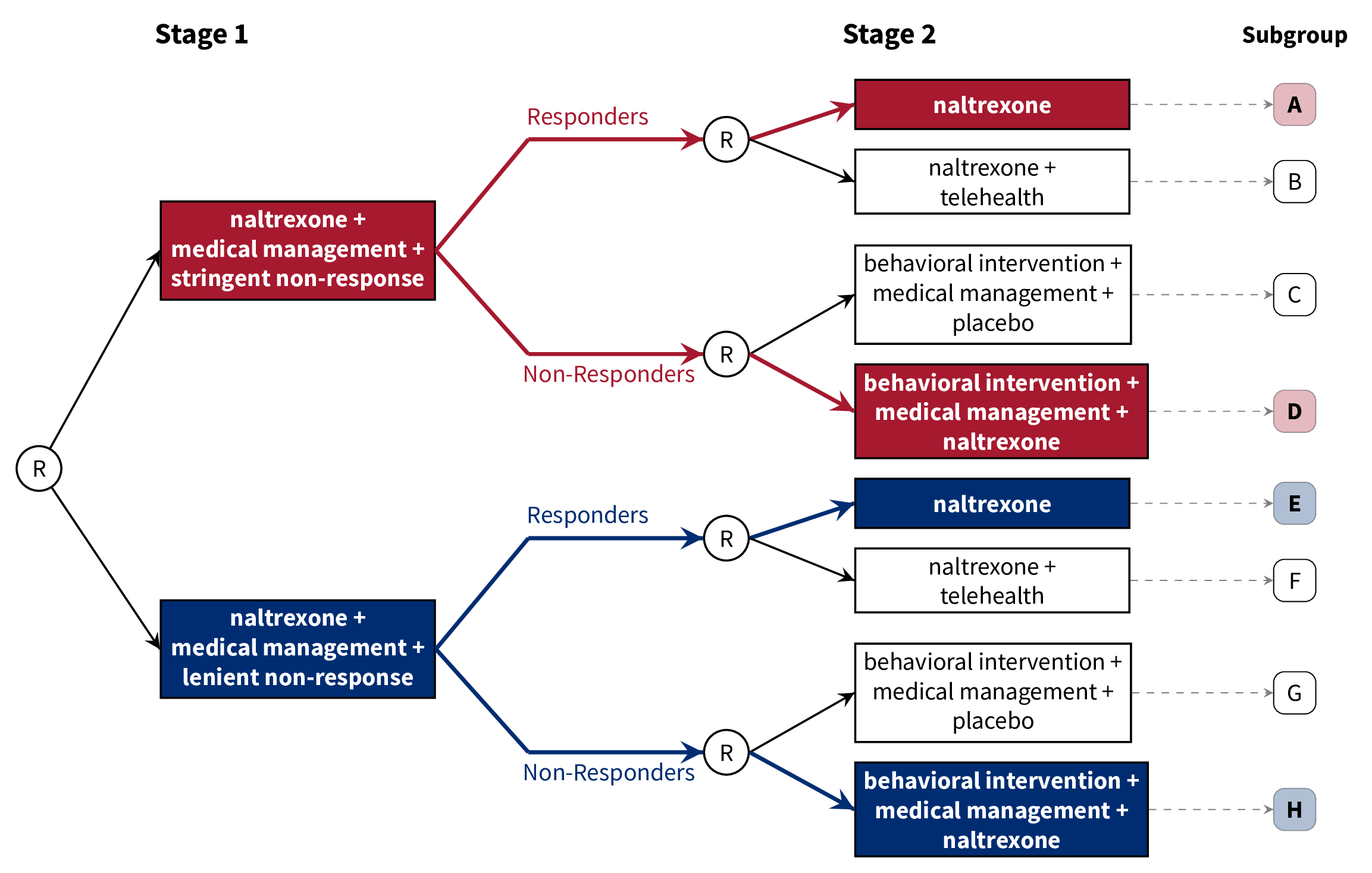

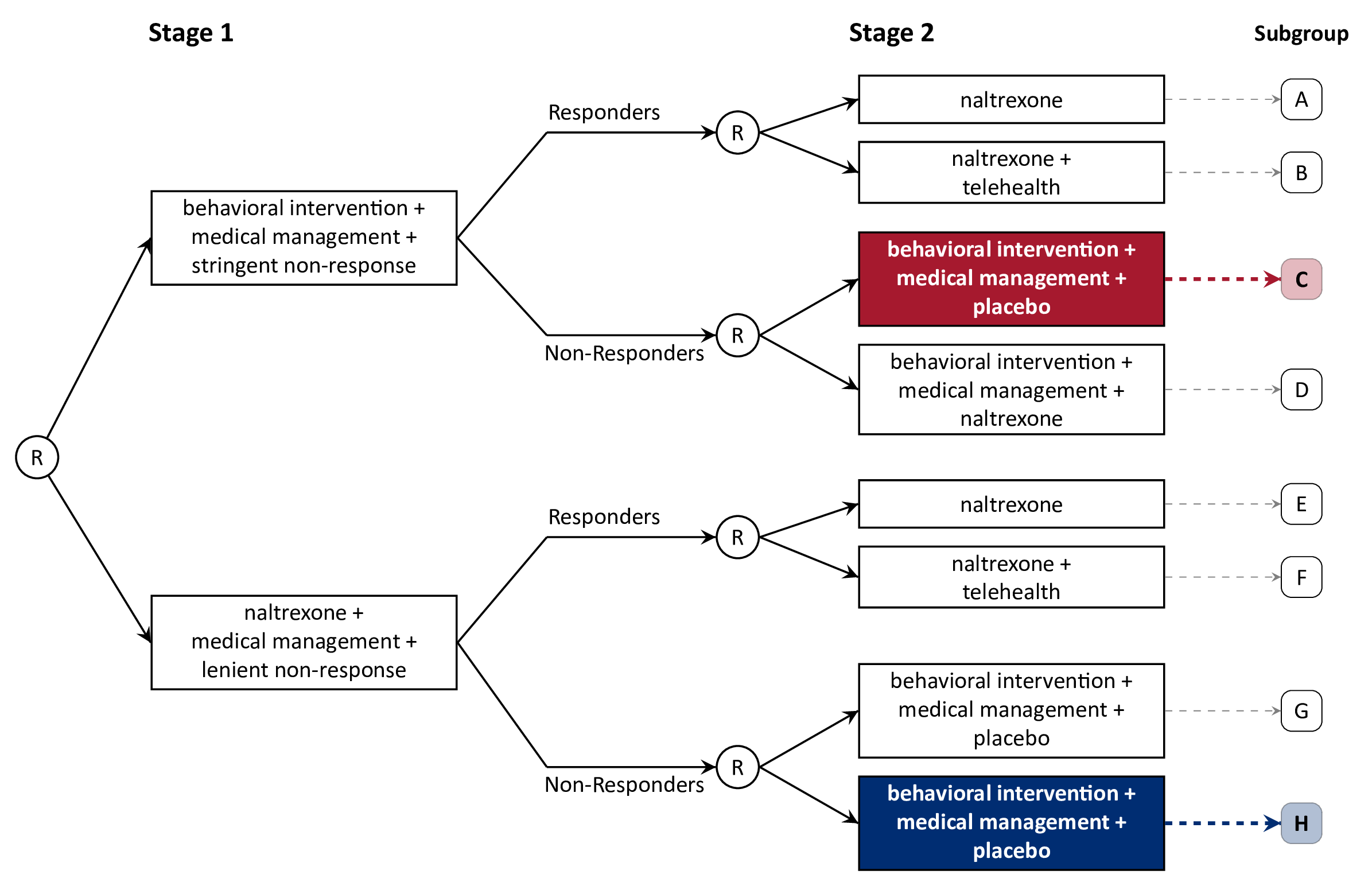

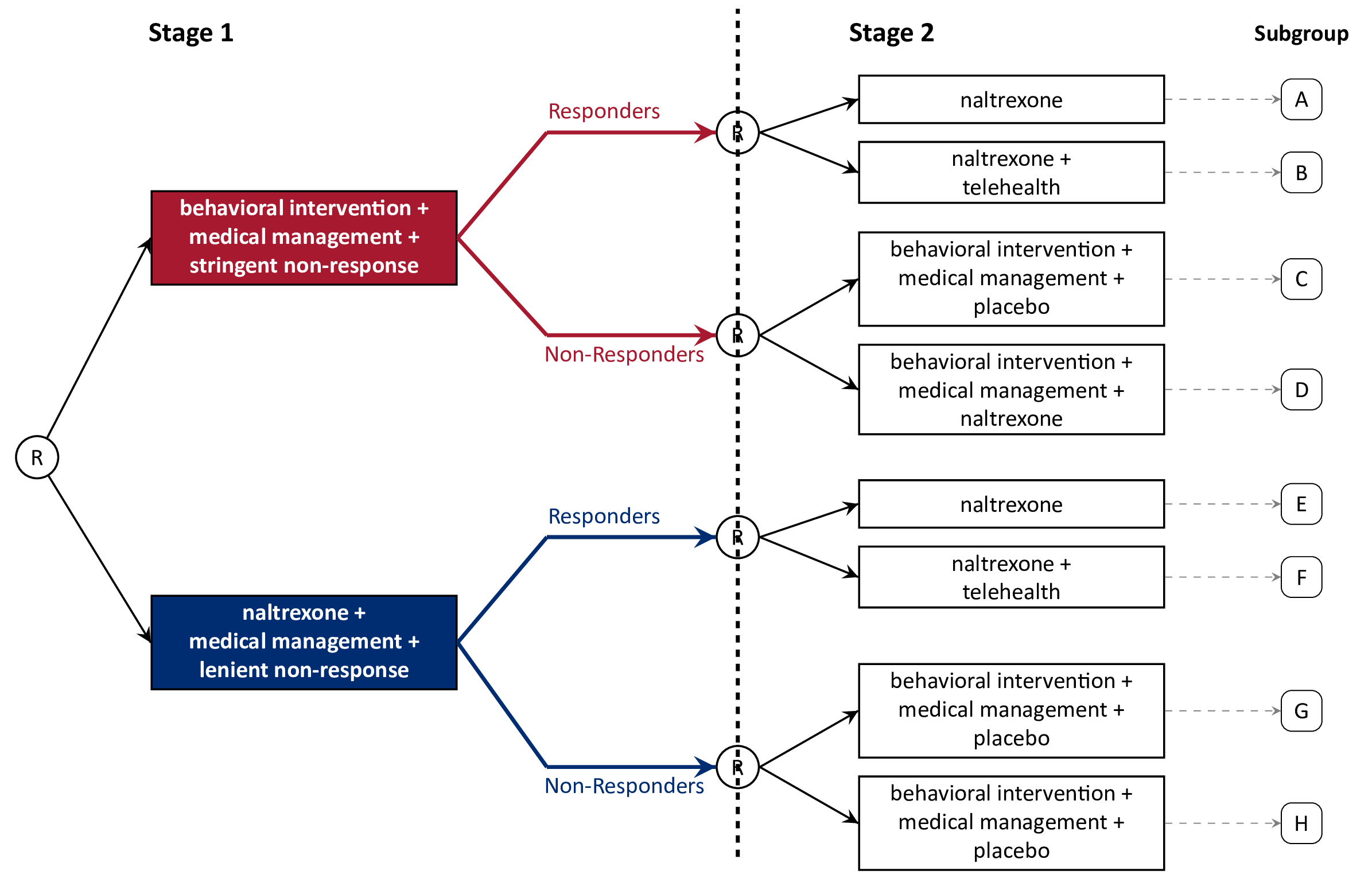

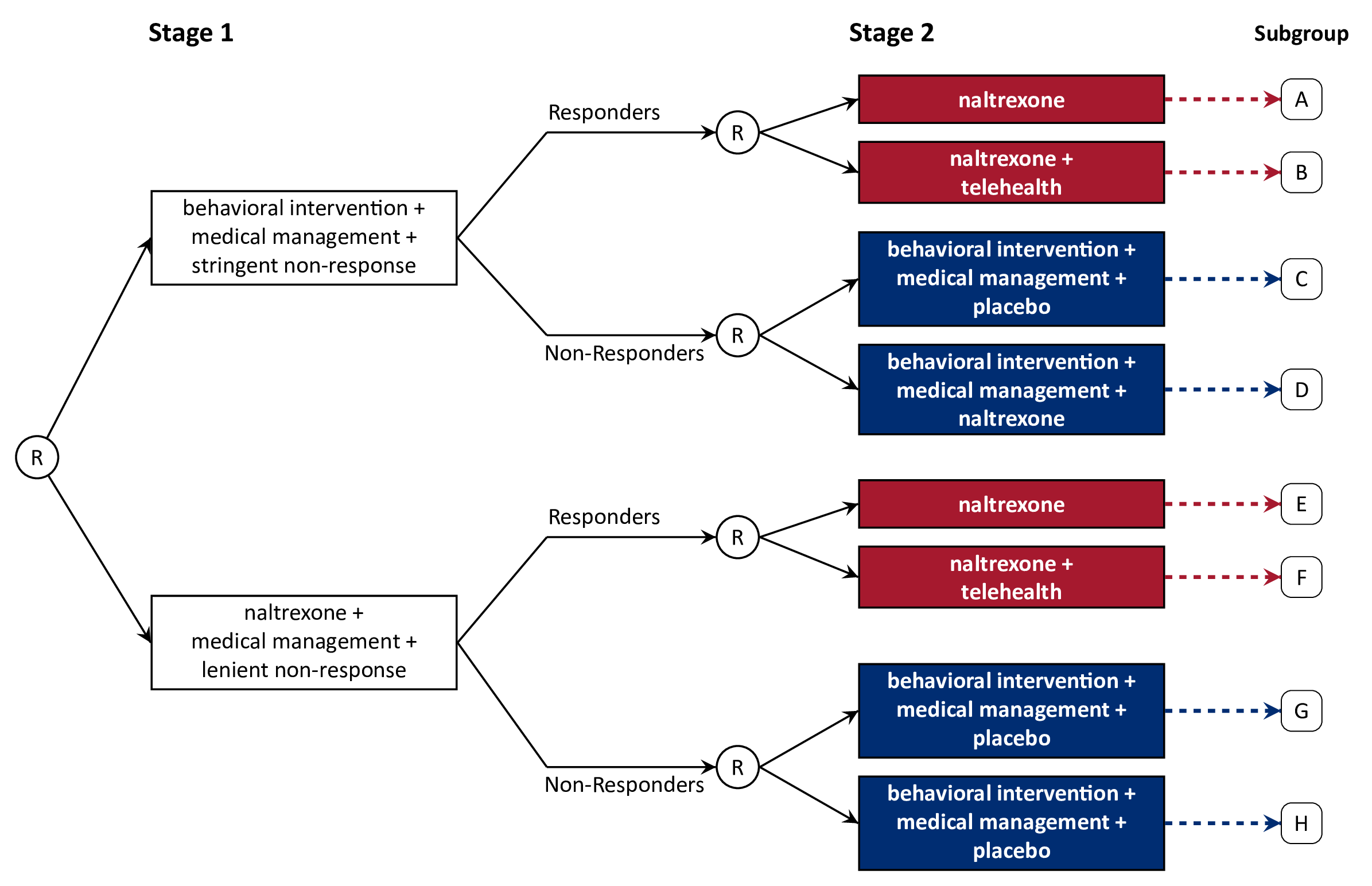

class: title title-slide # A Brief Introduction to Multi-Stage Trials for Developing Dynamic Treatment Regimens ### Nicholas J. Seewald, Ph.D. ### 11 March 2022 <br> .bottom.center[ MNeuroNetwork Lab Seminar<br> University of Michigan ] --- class: inverse, center, middle # Follow along! Slides are available at [https://slides.nickseewald.com/talk-mneuronet-2022](https://slides.nickseewald.com/talk-mneuronet-2022)  Materials are partially adapted from workshops given by the [d3lab](https://d3lab.isr.umich.edu) at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research and from <a name=cite-seewaldSequentialMultipleAssignment2021></a>[Seewald, Hackworth, and Almirall (2021)](https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52677-5_280-1). --- # What is a dynamic treatment regimen? A **dynamic treatment regimen (DTR)** is - an *intervention* design that - adapts the type, timing, intensity, or dose of treatment over time - according to a patient's specific and changing needs. -- In practice, a dynamic treatment regimen is a sequence of decision rules that can be used to guide how treatment can be adapted and readapted to an individual. -- .center[ ### Sounds a lot like clinical practice! ] -- **MANY other names**: adaptive intervention, adaptive treatment strategy, individualized treatment rule, treatment algorithm, individualized intervention... --- class: inverse, center, middle # A dynamic treatment regimen is an *intervention design*, NOT an experimental design. We'll talk about experiments soon! --- # 5 components of a DTR Dynamic treatment regimens consist of 1. Decision points 1. Tailoring variable(s) 1. Intervention options 1. Decision rule(s) 1. Proximal and distal outcomes --- # Example DTR: Alcohol Use Disorder - **Naltrexone** is known to diminish pleasurable effects of alcohol <a name=cite-oslinTargetingTreatmentsAlcohol2006></a>([Oslin, Berrettini, and O'Brien, 2006](https://doi.org/10/fgcfbk)) - Response to naltrexone is heterogeneous (adherence, biology, social support, etc.) <a name=cite-nahum-shaniSMARTDataAnalysis2017></a>([Nahum-Shani, Ertefaie, Lu, Lynch, McKay, Oslin, and Almirall, 2017](https://doi.org/10/ghpb9n)) - Heterogeneity necessitates a supportive intervention alongside naltrexone - **Medical management**: face-to-face clinical support + adherence monitoring - **Combined behavioral intervention**: targets patient's motivation for change, emphasizes social support <a name=cite-longabaughOriginsIssuesOptions2005></a>([Longabaugh, Zweben, Locastro, and Miller, 2005](https://doi.org/10/ghpb9f)) --- # Example DTR: Alcohol Use Disorder  -- 1. Decision points 1. Tailoring variable(s) 1. Intervention options 1. Decision rule(s) 1. Proximal and distal outcomes --- # Example DTR: Decision Points .fl.w-third[ A **decision point** is a time at which treatment might be adapted to the individual. - **Decision point 1:** Treatment outset — decide how to initiate treatment - **Decision point 2:** Adjust treatment after 8 weeks ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.vh-50[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Example DTR: Tailoring Variables .fl.w-third[ A **tailoring variable** is used to individualize treatment at each decision point. - "Static": age, baseline risk, etc. - "Dynamic": adherence to treatment, disease severity, etc. The DTR recommends an intervention option for each level of the tailoring variable. ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.vh-50[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Example DTR: Tailoring Variables .fl.w-third[ Here, the tailoring variable is the **number of self-reported heavy drinking days following treatment initiation**. - `\(\geq\)` 2 heavy drinking days `\(\rightarrow\)` _non-responder_ - `\(<\)` 2 heavy drinking days `\(\rightarrow\)` _responder_ ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.vh-50[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Some Notes on Tailoring Variables Note that the tailoring variable is _pre-specified_ and _well-defined_. Tailoring variables **are part of the intervention**! Should be based on _practical_, _ethical_, or _scientific_ considerations. - **Practical**: You might save more intense or costly intervention options for those who need it most (e.g., non-responders) - **Ethical**: You might have an ethical obligation to modify treatment for a particular subset of individuals - **Scientific**: You might have empirical evidence suggesting that responders need a different type of intervention than do non-responders --- # Example DTR: Intervention Options .fl.w-third[ - **Intervention options** at each decision point might be aspects of treatment: type, intensity, dose, delivery method, timing, etc. - Here, intervention options are combinations of _naltrexone_, _medical management_, and _combined behavioral intervention_ ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.vh-50.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Example DTR: Intervention Options .fl.w-third[ In subsequent stages, could be _adaptation strategies_ like "augment", "intensify" or "stay the course". ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.vh-50.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Example DTR: Decision Rules .fl.w-third[ A **decision rule** recommends an _intervention option_ for individuals at each decision point, possibly based on prior information (i.e., a tailoring variable) ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.vh-50.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Example DTR: Decision Rules .fl.w-third[ A **decision rule** recommends an _intervention option_ for individuals at each decision point, possibly based on prior information (i.e., a tailoring variable) ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.vh-50.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Example DTR: Proximal & Distal Outcomes A dynamic treatment regimen's design should be guided by both short-term (**proximal**) and long-term (**distal**) outcomes - **Distal outcomes** are the long-term goals of the DTR - Long-term, example DTR should reduce _likelihood of alcohol use relapse_ - **Proximal outcomes** are the near-term goals of the DTR; perhaps a mechanism by which we can achieve the distal outcome. - Short-term, we want to lower risk of relapse by reducing the _proportion of drinking and heavy-drinking days over 8 weeks after adaptation_ <a name=cite-leiSMARTDesignBuilding2012></a>([Lei, Nahum-Shani, Lynch, Oslin, and Murphy, 2012](https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152)) --- # Scientific Questions about DTRs Often unanswered questions about how to sequence and adapt interventions! Typically related to - relative effectiveness of different DTRs - relative effectiveness of different intervention options - how intervention options work with/against each other -- ### For example: 1. Which treatment option should the dynamic treatment regimen begin with? 1. How should we modify treatment for initial non-responders? 1. How should we modify treatment for initial responders? 1. How do we _define_ response/non-response? 1. How should we time decision points? --- # Alcohol Use Disorder: Scientific Questions - How do we define non-response to naltrexone in the context of a dynamic treatment regimen? - Unclear how many heavy drinking days indicate a need to augment treatment - What treatments should be offered following the initial intervention (naltrexone + medical management)? - More intense support for non-responders? - Do responders need a supportive intervention alongside naltrexone? -- .center[## Let's now discuss an experimental design which can help answer these questions] --- class: inverse, middle, center # Sequential, Multiple-Assignment Randomized Trials (SMARTs)  --- # SMARTs A **sequential, multiple-assignment randomized trial** is _one type_ of randomized trial design that can be used to answer questions at multiple stages of the development of a high-quality dynamic treatment regimen. -- The key feature of a SMART is that some (or all) participants are randomized _more than once_. --- # How do SMARTs inform DTR development? Randomizations in a SMART correspond to open scientific questions about constructing a dynamic treatment regimen! In ExTENd, - First randomization seeks to answer a question about definition of non-response - Second randomization in responders investigates whether lower-intensity medical management ("telehealth") is needed as maintenance therapy - Second randomization in non-responders looks at the effect of naltrexone in the context of combined behavioral intervention + medical management --- # Example: The ExTENd Study (PI: D. Oslin) .center[  ] --- # 8 DTRs "embedded" in ExTENd .center[  ] --- # 8 DTRs "embedded" in ExTENd .center[  ] --- # 8 DTRs "embedded" in ExTENd .center[  ] --- # 8 DTRs "embedded" in ExTENd .center[  ] --- # 8 DTRs "embedded" in ExTENd .center[  ] --- # Do I need a SMART? SMARTs are designed to answer questions about the development of high-quality dynamic treatment regimes. Consider a SMART if... 1. You want to develop a DTR 1. There are open questions preventing the construction of an effective DTR 1. There are open questions at _multiple decision points_ within a DTR -- If any of these aren't true, you don't need a SMART! --- # Do I need a SMART? ## What if we know what to do for responders? .center[  ] --- # Do I need a SMART? ## What if we know what to do for responders? .fl.w-third[ There are still questions about multiple stages of the development of a DTR. - What should we do first? - What should we do for non-responders? ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Do I need a SMART? ## What if we know what to do for responders? .fl.w-third[ There are still questions about multiple stages of the development of a DTR. - What should we do first? - What should we do for non-responders? A SMART **is** appropriate here: _some_ participants are randomized more than once. ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Do I need a SMART? ## What if we know what to do initially? .center[  ] --- # Do I need a SMART? ## What if we know what to do initially? .fl.w-third[ There are questions about only **one stage** of a dynamic treatment regimen . If there is no scientific question about how to initiate the dynamic treatment regimen, we do not need the initial randomization. ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Do I need a SMART? ## What if we know what to do initially? .fl.w-third[ We might instead run this trial with a run-in period on the initial intervention. This is **not** a SMART: all participants are randomized exactly once. ] .fl.w-two-thirds.dt.pa2[ .dtc.v-mid.tc[ .v-mid[ ] ] ] --- # Do I need a SMART? Not all research on dynamic treatment regimens requires a SMART! It may be appropriate to consider a "singly-randomized" alternative; see <a name=cite-almirallDevelopingOptimizedAdaptive2018></a>[Almirall, Kasari, McCaffrey, and Nahum-Shani (2018)](https://doi.org/10/gjh5tw). --- # A small misconception about SMARTs Sometimes, SMARTs are referred to as "adaptive" trials. This is not necessarily correct. - In an _adaptive trial_, data collected throughout the trial is used to modify _features of the trial itself_. (e.g., randomization probabilities, arms, etc.) - **SMARTs are typically _fixed_ designs.** All participants move through the trial as it was initially designed. In adaptive trials, the _trial_ is adaptive. SMARTs are designed to address questions about _interventions_ that are adaptive. See [Seewald, et al. (2021)](https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52677-5_280-1) for more details. --- # Recap: What do we know so far? So far, we've learned - what a dynamic treatment regimen is - some scientific questions one might ask about developing a dynamic treatment regimen - an experimental design that's useful for addressing questions related to multiple stages of dynamic treatment regimens (SMART) - When SMARTs may or may not be useful. .center[### Now, let's discuss some principles which guide the design of a high-quality SMART.] --- class: center middle inverse # Design and Analysis Considerations for SMARTs --- # More on Tailoring Variables Tailoring variables are often used to **restrict randomization** (recommend different intervention options to different subgroups of participants). Tailoring variables should be **well-justified**: remember, they're part of the DTRs! - Should be relatively easy to measure *in situ* - Assignment should be systematic Secondary data analysis (Q-learning) can be used to discover "candidate" tailoring variables for future work or more deeply tailored DTRs. You do **not** need to restrict randomization in a SMART! If you don't have good reason to embed a tailoring variable, don't do it. --- # Primary & Secondary Aims Focus on a few scientific aims about developing a high-quality DTR. - **Primary aim:** Choose sample size based on this aim - Commonly a comparison of groups of experimental conditions - Should be related to scientific questions about dynamic treatment regimens - **Secondary aims:** Leverage rich data on treatment sequences to further inform a more deeply-tailored DTR --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare initial intervention options in the context of a DTR .center[  ] --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare initial intervention options in the context of a DTR .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ Hypothetical hypothesis might be: > A stringent definition of non-response in the context of a dynamic treatment regimen will lead to fewer heavy drinking days, on average, than a lenient definition of non-response. ] --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare initial intervention options .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ - Analysis is just a two-group comparison of subgroups A-D vs. subgroups E-H - Sample size requirements are the same as for a two-arm RCT. ] --- # Design Considerations: Primary Aims ### Compare second-stage options among (non-)responders .center[  ] --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare second-stage options among (non-)responders .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ Hypothetical hypothesis: > Individuals who "respond" to naltrexone and medical management benefit more from naltrexone along with a telehealth intervention than naltrexone alone, on average, in terms of proportion of heavy drinking days after 8 weeks. ] --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare second-stage options among (non-)responders .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ - Analysis is a two-group comparison of subgroups A & E vs. subgroups B & F - Sample size is as for a two-group comparison, upweighted by response rate. ] --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare embedded dynamic treatment regimens .center[  ] --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare embedded dynamic treatment regimens .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ Hypothetical hypothesis: > The red DTR will lead to fewer heavy drinking days after 8 weeks, on average, as compared to the blue DTR. ] --- # Common Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Compare embedded dynamic treatment regimens .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ - Analysis is *slightly* more complicated, but still reasonable (think weighted regression) - Sample size formulae available (see additional resources) ] --- # Questionable Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Comparison of individual subgroups / experimental conditions .pull-left[ DTRs recommend treatments for every level of the tailoring variable. This is not a question about DTRs; therefore, it's not a strong motivation for a SMART. ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Questionable Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Comparison of response rates between first-stage intervention options .pull-left[ Not really about DTRs: ignores second-stage treatment. Maybe an interesting secondary analysis, but not a strong motivation for a SMART. ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Questionable Primary Aims for SMARTs ### Comparison of responders vs. non-responders .pull-left[ This is a non-randomized comparison: we did not experimentally assign response status. Not a question about DTRs - DTRs recommend treatment for both responders and non-responders. A non-randomized comparison does not motivate a randomized trial. ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Recap SMARTs are experimental designs which are used to address questions at multiple stages of the development of dynamic treatment regimens. Ultimately, the guiding principle of designing a SMART is "keep it simple". Primary aims of a SMART should be focused on developing dynamic treatment regimens. Sample size and analytic considerations for primary aims can often leverage familiar tools, and more advanced methods are available for more complex questions. --- # Sample Size Resources ## for comparing dynamic treatment regimens - **Continuous Outcomes:** <a name=cite-oettingStatisticalMethodologySMART2011></a><a name=cite-ogbagaberDesignSequentiallyRandomized2016></a>[Oetting, Levy, Weiss, and Murphy (2011)](#bib-oettingStatisticalMethodologySMART2011); [Ogbagaber, Karp, and Wahed (2016)](https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6747) - **Binary Outcomes:** <a name=cite-kidwellDesignAnalysisConsiderations2018></a>[Kidwell, Seewald, Tran, Kasari, and Almirall (2018)](https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2017.1386773) - **Survival Outcomes:** <a name=cite-fengSampleSizeTwostage2009></a><a name=cite-liSampleSizeFormulae2011></a>[Feng and Wahed (2009)](https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3593); [Li and Murphy (2011)](https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/asr019) - **Cluster-Randomized:** <a name=cite-necampComparingClusterlevelDynamic2017></a>[NeCamp, Kilbourne, and Almirall (2017)](https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280217708654) - **Longitudinal:** <a name=cite-seewaldSampleSizeConsiderations2020></a>[Seewald, Kidwell, Nahum-Shani, Wu, McKay, and Almirall (2020)](https://doi.org/10/gf85ss) - **Finding the best embedded DTR:** <a name=cite-artmanPowerAnalysisSMART2018></a>[Artman, Nahum-Shani, Wu, Mckay, and Ertefaie (2018)](https://doi.org/10/ggth75) --- # Additional Reading Materials from 3-day workshop on SMARTs and DTRs: <https://d3lab.isr.umich.edu/workshop/getting-smart-about-adaptive-interventions-in-education-2019/> More in-depth, full book on DTRs: Kosorok, M.R., and E.E.M. Moodie, eds. 2015. Adaptive Treatment Strategies in Practice: Planning Trials and Analyzing Data for Personalized Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611974188. Overview of many different SMART in the field: Lei, H., I. Nahum-Shani, K. Lynch, D. Oslin, and S.A. Murphy. “A ‘SMART’ Design for Building Individualized Treatment Sequences.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 8, no. 1 (2012): 21–48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152. --- # Additional Reading A nice introduction to SMARTs and DTRs in behavioral science: Nahum-Shani, I., M. Qian, D. Almirall, W.E. Pelham, B. Gnagy, G.A. Fabiano, J.G. Waxmonsky, J. Yu, and S.A. Murphy. “Experimental Design and Primary Data Analysis Methods for Comparing Adaptive Interventions.” Psychological Methods 17, no. 4 (2012): 457–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029372. An introduction to "Q-learning" for building more "deeply tailored" DTRs: Nahum-Shani, I., M. Qian, D. Almirall, W.E. Pelham, B. Gnagy, G.A. Fabiano, J.G. Waxmonsky, J. Yu, and S.A. Murphy. 2012. “Q-Learning: A Data Analysis Method for Constructing Adaptive Interventions.” Psychological Methods 17 (4): 478–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029373. --- # References <a name=bib-almirallDevelopingOptimizedAdaptive2018></a>[Almirall, D. et al.](#cite-almirallDevelopingOptimizedAdaptive2018) (2018). "Developing Optimized Adaptive Interventions in Education". In: _Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness_ 11.1, pp. 27-34. ISSN: 1934-5747. DOI: [10/gjh5tw](https://doi.org/10%2Fgjh5tw). <a name=bib-artmanPowerAnalysisSMART2018></a>[Artman, W. J. et al.](#cite-artmanPowerAnalysisSMART2018) (2018). "Power Analysis in a SMART Design: Sample Size Estimation for Determining the Best Embedded Dynamic Treatment Regime". In: _Biostatistics_. DOI: [10/ggth75](https://doi.org/10%2Fggth75). <a name=bib-fengSampleSizeTwostage2009></a>[Feng, W. et al.](#cite-fengSampleSizeTwostage2009) (2009). "Sample Size for Two-Stage Studies with Maintenance Therapy". In: _Statistics in Medicine_ 28.15, pp. 2028-2041. ISSN: 0277-6715. DOI: [10.1002/sim.3593](https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fsim.3593). <a name=bib-kidwellDesignAnalysisConsiderations2018></a>[Kidwell, K. M. et al.](#cite-kidwellDesignAnalysisConsiderations2018) (2018). "Design and Analysis Considerations for Comparing Dynamic Treatment Regimens with Binary Outcomes from Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trials". In: _Journal of Applied Statistics_ 45.9, pp. 1628-1651. ISSN: 0266-4763, 1360-0532. DOI: [10.1080/02664763.2017.1386773](https://doi.org/10.1080%2F02664763.2017.1386773). --- # References <a name=bib-leiSMARTDesignBuilding2012></a>[Lei, H. et al.](#cite-leiSMARTDesignBuilding2012) (2012). "A "SMART" Design for Building Individualized Treatment Sequences". In: _Annual Review of Clinical Psychology_ 8.1, pp. 21-48. ISSN: 1548-5943, 1548-5951. DOI: [10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152](https://doi.org/10.1146%2Fannurev-clinpsy-032511-143152). <a name=bib-liSampleSizeFormulae2011></a>[Li, Z. et al.](#cite-liSampleSizeFormulae2011) (2011). "Sample Size Formulae for Two-Stage Randomized Trials with Survival Outcomes". In: _Biometrika_ 98.3, pp. 503-518. ISSN: 00063444. DOI: [10.1093/biomet/asr019](https://doi.org/10.1093%2Fbiomet%2Fasr019). <a name=bib-longabaughOriginsIssuesOptions2005></a>[Longabaugh, R. et al.](#cite-longabaughOriginsIssuesOptions2005) (2005). "Origins, Issues and Options in the Development of the Combined Behavioral Intervention." In: _J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl._, pp. 179-187. ISSN: 0363-468X. DOI: [10/ghpb9f](https://doi.org/10%2Fghpb9f). --- # References <a name=bib-nahum-shaniSMARTDataAnalysis2017></a>[Nahum-Shani, I. et al.](#cite-nahum-shaniSMARTDataAnalysis2017) (2017). "A SMART Data Analysis Method for Constructing Adaptive Treatment Strategies for Substance Use Disorders". In: _Addiction_ 112.5, pp. 901-909. ISSN: 1360-0443. DOI: [10/ghpb9n](https://doi.org/10%2Fghpb9n). <a name=bib-necampComparingClusterlevelDynamic2017></a>[NeCamp, T. et al.](#cite-necampComparingClusterlevelDynamic2017) (2017). "Comparing Cluster-Level Dynamic Treatment Regimens Using Sequential, Multiple Assignment, Randomized Trials: Regression Estimation and Sample Size Considerations". In: _Statistical Methods in Medical Research_ 26.4, pp. 1572-1589. ISSN: 0962-2802, 1477-0334. DOI: [10.1177/0962280217708654](https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0962280217708654). <a name=bib-oettingStatisticalMethodologySMART2011></a>[Oetting, A. I. et al.](#cite-oettingStatisticalMethodologySMART2011) (2011). "Statistical Methodology for a SMART Design in the Development of Adaptive Treatment Strategies". In: _Causality and Psychopathology: Finding the Determinants of Disorders and Their Cures_. Ed. by P. E. Shrout, K. M. Keyes and K. Ornstein. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 179-205. ISBN: 978-0-19-975464-9. --- # References <a name=bib-ogbagaberDesignSequentiallyRandomized2016></a>[Ogbagaber, S. B. et al.](#cite-ogbagaberDesignSequentiallyRandomized2016) (2016). "Design of Sequentially Randomized Trials for Testing Adaptive Treatment Strategies". In: _Statistics in Medicine_ 35.6, pp. 840-858. DOI: [10.1002/sim.6747](https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fsim.6747). <a name=bib-oslinTargetingTreatmentsAlcohol2006></a>[Oslin, D. W. et al.](#cite-oslinTargetingTreatmentsAlcohol2006) (2006). "Targeting Treatments for Alcohol Dependence: The Pharmacogenetics of Naltrexone". In: _Addiction Biology_ 11.3-4, pp. 397-403. ISSN: 1369-1600. DOI: [10/fgcfbk](https://doi.org/10%2Ffgcfbk). <a name=bib-seewaldSequentialMultipleAssignment2021></a>[Seewald, N. J. et al.](#cite-seewaldSequentialMultipleAssignment2021) (2021). "Sequential, Multiple Assignment, Randomized Trials (SMART)". In: _Principles and Practice of Clinical Trials_. Ed. by S. Piantadosi and C. L. Meinert. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1-19. ISBN: 978-3-319-52677-5. DOI: [10.1007/978-3-319-52677-5_280-1](https://doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-319-52677-5_280-1). --- # References <a name=bib-seewaldSampleSizeConsiderations2020></a>[Seewald, N. J. et al.](#cite-seewaldSampleSizeConsiderations2020) (2020). "Sample Size Considerations for Comparing Dynamic Treatment Regimens in a Sequential Multiple-Assignment Randomized Trial with a Continuous Longitudinal Outcome". In: _Stat Methods Med Res_ 29.7, pp. 1891-1912. ISSN: 0962-2802. DOI: [10/gf85ss](https://doi.org/10%2Fgf85ss). --- class: center, inverse, middle # Reach out with questions (or ideas)! <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M464 64H48C21.49 64 0 85.49 0 112v288c0 26.51 21.49 48 48 48h416c26.51 0 48-21.49 48-48V112c0-26.51-21.49-48-48-48zm0 48v40.805c-22.422 18.259-58.168 46.651-134.587 106.49-16.841 13.247-50.201 45.072-73.413 44.701-23.208.375-56.579-31.459-73.413-44.701C106.18 199.465 70.425 171.067 48 152.805V112h416zM48 400V214.398c22.914 18.251 55.409 43.862 104.938 82.646 21.857 17.205 60.134 55.186 103.062 54.955 42.717.231 80.509-37.199 103.053-54.947 49.528-38.783 82.032-64.401 104.947-82.653V400H48z"/></svg> [nseewal1@jhu.edu](mailto:nseewal1@jhu.edu) <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M459.37 151.716c.325 4.548.325 9.097.325 13.645 0 138.72-105.583 298.558-298.558 298.558-59.452 0-114.68-17.219-161.137-47.106 8.447.974 16.568 1.299 25.34 1.299 49.055 0 94.213-16.568 130.274-44.832-46.132-.975-84.792-31.188-98.112-72.772 6.498.974 12.995 1.624 19.818 1.624 9.421 0 18.843-1.3 27.614-3.573-48.081-9.747-84.143-51.98-84.143-102.985v-1.299c13.969 7.797 30.214 12.67 47.431 13.319-28.264-18.843-46.781-51.005-46.781-87.391 0-19.492 5.197-37.36 14.294-52.954 51.655 63.675 129.3 105.258 216.365 109.807-1.624-7.797-2.599-15.918-2.599-24.04 0-57.828 46.782-104.934 104.934-104.934 30.213 0 57.502 12.67 76.67 33.137 23.715-4.548 46.456-13.32 66.599-25.34-7.798 24.366-24.366 44.833-46.132 57.827 21.117-2.273 41.584-8.122 60.426-16.243-14.292 20.791-32.161 39.308-52.628 54.253z"/></svg> [@nickseewald](https://twitter.com/nickseewald) <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M326.612 185.391c59.747 59.809 58.927 155.698.36 214.59-.11.12-.24.25-.36.37l-67.2 67.2c-59.27 59.27-155.699 59.262-214.96 0-59.27-59.26-59.27-155.7 0-214.96l37.106-37.106c9.84-9.84 26.786-3.3 27.294 10.606.648 17.722 3.826 35.527 9.69 52.721 1.986 5.822.567 12.262-3.783 16.612l-13.087 13.087c-28.026 28.026-28.905 73.66-1.155 101.96 28.024 28.579 74.086 28.749 102.325.51l67.2-67.19c28.191-28.191 28.073-73.757 0-101.83-3.701-3.694-7.429-6.564-10.341-8.569a16.037 16.037 0 0 1-6.947-12.606c-.396-10.567 3.348-21.456 11.698-29.806l21.054-21.055c5.521-5.521 14.182-6.199 20.584-1.731a152.482 152.482 0 0 1 20.522 17.197zM467.547 44.449c-59.261-59.262-155.69-59.27-214.96 0l-67.2 67.2c-.12.12-.25.25-.36.37-58.566 58.892-59.387 154.781.36 214.59a152.454 152.454 0 0 0 20.521 17.196c6.402 4.468 15.064 3.789 20.584-1.731l21.054-21.055c8.35-8.35 12.094-19.239 11.698-29.806a16.037 16.037 0 0 0-6.947-12.606c-2.912-2.005-6.64-4.875-10.341-8.569-28.073-28.073-28.191-73.639 0-101.83l67.2-67.19c28.239-28.239 74.3-28.069 102.325.51 27.75 28.3 26.872 73.934-1.155 101.96l-13.087 13.087c-4.35 4.35-5.769 10.79-3.783 16.612 5.864 17.194 9.042 34.999 9.69 52.721.509 13.906 17.454 20.446 27.294 10.606l37.106-37.106c59.271-59.259 59.271-155.699.001-214.959z"/></svg> [nickseewald.com](https://www.nickseewald.com)